NEWS

Dal Niente and the Magical Gloves!

Katie Schoepflin, Dal Niente clarinetist, discusses the unique and surreal preparation of Marcin Pączkowski’s Deep Decline at the University of Washington Residency last October.

Dal Niente and the Magical Gloves!

by Katie Schoepflin

Preparing for and performing the world premiere of Marcin Paczkowski’s Deep Decline at the University of Washington, Oct. 30 was a unique and surreal experience. The prep with my colleagues in Chicago was straight forward as the piece is full of beautiful melodies and phrasing that is intuitive. We were instructed to skip over the large sections that included electronic components as they were reliant upon the software Marcin had been building. I was surprised to find out how prominent and vital a role the electronics played in this piece. There have been times when I’ve felt that strapping on a microphone and playing through some filters made for some cool sound effects, and that was the extent of their purpose. But this piece came to life for me when we started sound checking the electronic sections. After wading through technical difficulties that dominated the first couple of hours of our rehearsal in Seattle, we were rewarded with super powers which Marcin bestowed upon each of us.

Before I get into the super powers, let me set the scene. This was our first rehearsal at UW, after a long, painfully early flight from Chicago. We had no idea what to expect with this piece. First came out the clip-on mics and second, the magical gloves. We each wore a handmade fingerless glove on our right hand which, secured with safety pins, had a sensor inside. The Michael Jackson references began immediately, and ‘Annie are you OK’ became the residency’s theme song (for better or for worse) for the duration of our stay.

Marcin’s sensors react to each performer’s individual movements, and he sets their level of sensitivity according to how much an individual naturally moves while playing. The idea is to have them set in a way that allows the performer to trigger the electronics without having to move wildly about, but not so sensitive that, when sitting still, the sensor will pick up motion from, say, breathing. This was the first soundcheck I had ever participated in where I needed to pretend to play my instrument and I was struck by how cool and comical it was. The temptation was to move a lot more than I would normally. The more I tried to move naturally, the less I felt like I had any concept of how I actually move when I play. They are so tied into each other that doing one without the other feels nonsensical. I feel a tiny bit more sympathetic towards actors who have had to pretend to play instruments in films now that I’ve experienced it myself.

I’d like to state for the record: It is always a good idea to give the conductor a solo. The times when Michael Lewanski has crossed over into performing with the ensemble have all been exciting moments. The first electronics section featured solos by each performer. One after another, we took turns playing short fragments and contorting our own solos with our sensors. This section culminated in a climactic conducting solo, in which Michael controlled the electronics with the velocity and direction of his beating patterns.

Near the end of the piece, recorded material from an earlier section overlapped slightly with our live playing, and the two seamlessly cross-faded into each other. The goal was to disguise that anything was changing. The first real indication the audience had that we were not playing was when we all slowly stopped moving, and the music wound down, dropping in pitch and speed until there was silence. And then we started right back up again, moving, not playing, a row of wind-up toys holding instruments. It was awesome.

A little Q and A with Marcin…

Q: What went into constructing the gloves?

A: Each of the gloves (or adapted headbands actually) contains a custom built circuit that includes a sensor - 3-axis accelerometer, a microcontroller with wireless radio that's transmitting data, and a battery. Information about acceleration (rate of change of the speed of hand's movement) is transmitted continuously to the computer for each of the players, as well as the conductor. I started thinking about using physical gestures for controlling music about 3 years ago, as a way to incorporate my education and activity as a conductor into my computer music practice. In 2013 I created a piece "Restrained meters" jointly with a dancer/choreographer Wilson Mendieta, where he was wearing the sensors and his movement was influencing computer-generated sound. Later I started using sensors myself in a conducting-like project which developed into the piece "...where odd things are kept". Then I used them in the solo percussion piece "Percussivometers", where the player's movements were influencing sound transformations in realtime. So I'd say that it was 3 years of on-off research and development, along with some electronics and programming, that went into making the gloves.

Q: Can you describe any meaning, story, inspiration behind writing this piece?

A: There’s no clear story behind the piece. However, like with any creative process, the piece itself is a mirror of personal experiences, mediated through music. Struggles, frustrations, moments of peace and melancholy all emerge through the elements of the composition.

Q: Is there a relationship between the tonal, gentle melodies and the by-product of the quick, harsh-sounding electronic outbursts?

A: These two are results of 2 different directions of development in the piece. What you describe as harsh-sounding electronic outbursts are developed from my previous experiments with improvisation with the computer and aesthetically relate to those earlier improvising pieces. Now the more tonal section was composed as a "vehicle" to carry the underlying variations of rhythmic density, which were algorithmically structured throughout it. Finally, the more calm nature of this section helped with fusing the acoustic and the computer playback sounds.

Watch video of Dal Niente's performance of Marcin's piece here!

Fragmentary Thoughts on Kate Soper’s “Voices from the Killing Jar” at NUNC

Michael Lewanski offers personal insights into Kate Soper's Voices from the Killing Jar in advance of Dal Niente's performance at the Northwestern New Music Conference (NUNC).

At an event like the Northwestern New Music Conference (NUNC!) one finds oneself asking the question “what is music?” every 5 minutes or so. Though I’m sure it wasn’t intentional, that Ensemble Dal Niente will perform excerpts from Kate Soper’s Voices from the Killing Jar at the end of our residency on the conference seems fitting: this is a work that has a lot to say about what music is, and, as it should be, it’s complicated.

Kate says the following about her work: "A killing jar is a tool used by entomologists to kill butterflies and other insects without damaging their bodies: a hermetically sealable glass container, lined with poison, in which the specimen will quickly suffocate. Voices from the Killing Jar is a seven-movement work for vocalist and ensemble which depicts a series of female protagonists who are caught in their own kinds of killing jars: hopeless situations, inescapable fates, impossible fantasies, and other unlucky circumstances."

This is an ambitious, striking conception, one that invites imaginative analogies and connections between characters both historical and fictional from widely varying cultures and times. The notion of a killing jar, though, also has a deeply immediate, visceral sense -- the music and the musicians are implicated as well. The composition is only rarely constructed to accompany the soprano. More often, it mimics or mirrors or expands upon her pitches and rhythms -- as if to amplify or comment on something she is singing, as if to inflect this or that thought or feeling in a way that gives it a heightened significance, emphasizing the extent to which the very mode of expression is part of whatever trap she is caught in. The music and the musicians can never simply let the soprano "be;" rather, they're always invading her voice, changing it, distorting it. (In some cases the distortion is quite literal -- electronic processing changes the vocal timbre into something artificial, alien, disembodied.) They force her into a musical situation that is not a product of her body, but an encounter between her subjectivity and an other whose will seems mysterious and capricious. Even the very instrumentation of the piece -- featuring the triangle, crotales, and piccolo above her register, and the saxophone, violin, and piano often below -- find her put in an uncomfortable middle.

Musical style sometimes comes across as a vehicle for expression; sometimes it seems political; sometimes it seems otherwise polemical. We’ve seen all of the above at NUNC. In Kate’s piece, it is at least partially a menace, a prison, an enactment of forces of repression. For instance, in the movement entitled Mad Scene: Emma Bovary the soprano performs operatic fragments and vocal warm-ups with a mechanistic repetition. These aren’t innocently deployed musical gestures that are merely conventional: they come across as brutally preparing the soprano to be the object of desire -- indicting you as an audience member just while you are one. What to say about the fact that these gestures become increasingly frenzied? Is that liberating? Or is the narrative subject just being driven crazy by things beyond her control?

In the The Owl and the Wren: Lady MacDuff the style of an ostensibly straightforward Renaissance dance is used to cover up and paper over the brutal murder of the title character and her children. Of course, it the dance is not simple and straightforward. It’s metrically unstable and written in the soprano’s low register (so she that her music is occasionally covered up). The seeming period-appropriate addition of the recorder becomes sinister as the overblown timbre becomes frantic, inviting speculations as to whether it is mimetic of children screaming, be they the Wren’s chicks or Lady MacDuff’s children. The music seems to say that style, as manifestation of culture, is what allows such barbarity to be normalized. (Feel free to contemplate, in this context, the ironies in my use of the word “barbarity,” and its fabled etymology.)

Mostly strikingly ambiguous is the last movement: Her Voice is Full of Money (A Deathless Song): Daisy Buchanan. The soprano both is and is not the famously shallow and self-centered character from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby -- on the one hand, the singer speaks Daisy’s lines, surrounded by sounds that may initially seem reminiscent of the “romantic outdoors” that cause her to be “paralyzed with happiness.” To end the work, though, the very same soprano flatly states that “her voice is full of money” (referring to the character she once portrayed), making the open’s metallic triangle, bells, crotales, and inside-the-piano sounds seem like the jangle of coins.

It would be woefully oversimplified to read soprano of Voices from the Killing Jar simply as a victim. This is a work by a female composer who was also, initially, the singer. Thus, there is a very literal and multi-layered assertion of control by the artist over the the materials, tradition, and history she has inherited. The soprano is not straightforwardly a powerless figure who is merely put upon; but neither is the work self-deceptively confident about its possible achievements. The history of culture is too complicated for that.

I was not struck until afterwards by a change Kate made in our rehearsal the other day -- she altered the writing of some voice-accompanimental violin octaves to be, instead, a single line in the instrument’s very high register. The texture, I only later realized, reminded me of Richard Strauss’s solo violin writing in his tone poems when he patronizingly and misogynistically attempts to portray women. I doubt this invocation was intentional on Kate’s part (though I could be wrong). But sometimes culture does that to you, and that Kate’s piece does not make facile claims, but rather manipulates inherited musical material in sophisticated ways is precisely the work’s strength. The music that closes the work continually returns to an open 5th: C-G, as if making an attempt at or a reference to C major, history’s most optimistic key. But there is no third of the chord, and there are too many problematizing pitches in the highly figurative piano, flute and saxophone parts that create the sense that a minor mode lurks around the corner. Thus, the music remains in an untranscended state; indeed, as does our whole, continually developing artform.

Finally: I haven’t run any of these theories by Kate, and I could be wrong about everything. I guess, though, I don’t mind being wrong if it prompts someone to think and feel this piece a little bit deeper.

-- Michael Lewanski

Vanishing into the Clouds: Dal Niente at ICMC

Ammie Brod, Dal Niente violist, recaps the 2015 International Computer Music Conference last month!

Vanishing into the Clouds: Dal Niente at ICMC

by Ammie Brod

I like doing things that push me to learn new skills, or that use skills that I already have in new and interesting ways. This is, in part, what drew me to new music in the first place—I love the more or less constant innovation taking place within the art form. Whatever else I may believe about the world at large I can rest assured that there will always be something new to learn, and that knowledge is a springboard for excitement and inspiration.

I was one of six members of Dal Niente who attended the International Computer Music Conference at the University of North Texas in Denton at the end of September. ICMC was an unusual experience for us as an ensemble—usually when we travel, we’re rehearsing and performing as a group, but this time almost all of our performances were for solo instruments and electronics. The conference itself was a jam-packed experience for all involved, with 31 concerts, as well as a large number of paper presentations, demonstrations, and installations, all in just seven days. (Hat tip to the staff: In the concerts I was able to attend there was only one real technological blip, which is highly impressive given that nearly every piece contained a technological component.) The Nientes alone performed twenty different pieces in six different performances during our two-day stay.

I wasn't sure exactly what to expect at a computer music conference, a genre that I'm admittedly less familiar with than other areas of contemporary performance. In particular, playing solo works with live electronics was an experience that I hadn't had yet, and as I worked on my parts at home and listened to recordings and communicated with composers, I felt simultaneously prepared and aware that there was going to be an unknown factor to the performance: I wouldn't be able to experience the piece in its entirety until just before the show, when I finally got to hear my part paired with its electronics and explore how I wanted to interact with the,. All of my pieces involved my performance being run through various programs, under the supervision of either the composer or another knowledgeable party, and then manipulated or incorporated into an electronic texture. Essentially, I would be playing against my own sounds (among other things), in some cases making artistic decisions on the spot depending on the flexibility of the notation and what I was hearing in real time.

I played three solo pieces during my time at ICMC, all quite different. Mikel Kuehn's Colored Shadows combined notated lyrical passages with a certain amount of interpretive freedom—there are several improvised sections on open strings where the performer chooses from a number of different gestures in order to augment and interplay with the electronic textures that are building up in the performance space. Joel Hunt’s Material, on the other hand, begins with quiet percussive effects, building from unpitched sounds to defined pitched phrases; I tapped different parts of my fingers in various rhythms on the body of the instrument, tapped the bridge with my fingernail, and knocked on the front before finally moving into more melodic material. As I played (at a bar, trying to make sure my tapping was making it over the clink of glasses and small talk), my own textures leapt out at me, finally building to a roar that lasted until I reasserted myself with a quietly moving line, ending with a gentle decrescendo into silence.

All of that, as well as performances of two ensemble pieces by Clarence Barlow and Johannes Kretz, took place on our first day at the conference. I only had one piece scheduled for the second day, Jacob Sudol’s Vanishing into the Clouds. Jacob’s piece begins with a series of long tones (at one point I played an open C string for a minute and a half) with subtle timbral shifts, varying the bow speed, pressure and placement to change the quality of a single note over a set period of time. Many of the notes are unstable, so the timbral shifts bring out different pitches and overtones over the course of time. The piece eventually moves into a series of subtle microtonal shifts played high on the D string, a range and placement that robs them of some of their warmth, while still asking the performer to phrase and shape the line. The contrast between the somewhat flattened nature of the notes and the desire to express something through them had been difficult, and I was interested to meet their composer and see what more I could learn by talking with him in person.

There are conversations about music that focus on pragmatic things (how to produce a certain sound, what overall aesthetic the composer was writing within) and there are conversations that reach a step beyond that, into a realm of excitement and exploration and inspiration. My conversation with Jacob moved seamlessly between those realms, from pinning down a specific timbre to discussions of how I’d be interacting with the electronics to something larger, a feeling about what the piece was meant to convey. I couldn’t put into words, but the discussion made it come together for me in a new way. It felt like an idea coming into focus, a clarity of interpretation that I’d been trying to reach on my own but hadn’t quite hit yet. The microtonal section I’d been struggling with came together, and I could feel that my brain and body finally knew how to produce the sound I wanted to create. It was, in a word, thrilling.

I carried that feeling with me into that evening’s performance, and it was deeply satisfying to not only present it to a live audience but to also hear it reflected back at me through Jacob’s electronics. I played over a chorus of textures created in part from the sounds I’d produced, and I felt deeply calm and present onstage. As the last almost inaudible harmonic faded out, I felt like something had been accomplished, and communicated, and learned.

When Dal Niente attended the International Summer Courses in Darmstadt, Germany, we were identified not as musicians or performers but as interpreters. To me, that distinction has always felt important—it feels like I’ve been given an investment in the creative process of a performance that isn’t always acknowledged, and it’s something I try to live up to when I play. In Texas, I felt that I succeeded.

Commissioning and Performing New Music for Horn

Matt Oliphant talks about commissioning and performing new music on the horn and his upcoming Dal Niente Presents on Sunday, October 18 at Constellation.

Commissioning and Performing New Music for Horn

by Matt Oliphant

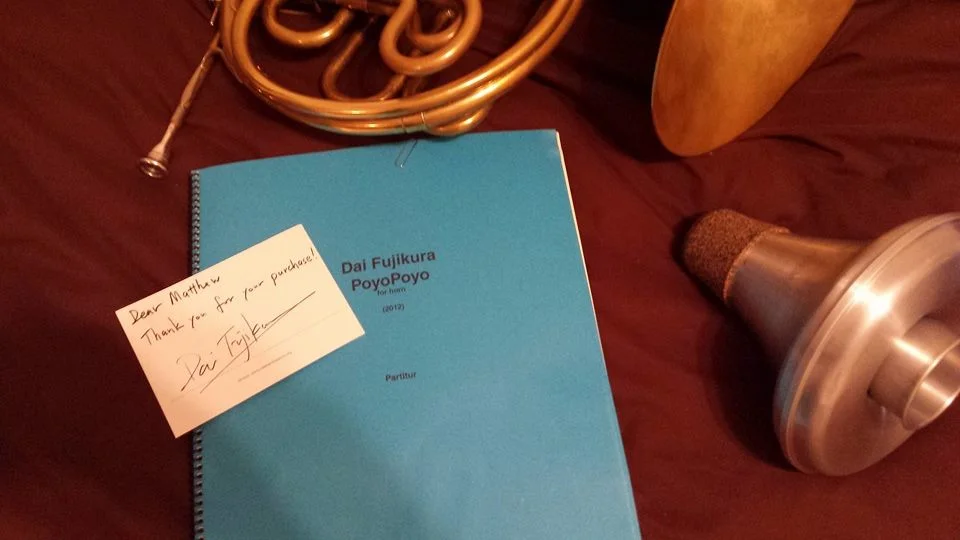

When I scheduled a performance of Dai Fujikura's PoyoPoyo for fall of 2014, I was initially surprised to find out that I would be giving the US premiere. Surprised because the piece (written in 2012) is stunningly beautiful and unique and utilizes otherwise untapped tone colors (a lot of which come from the use of a bass trombone harmon - aka wah-wah - mute). And yet I shouldn't have been surprised, because performances of contemporary solo horn repertoire are few and far between. Which is a shame. The horn is an incredibly versatile instrument and lends itself to many techniques of contemporary composition, if only people could or would take advantage of it.

The sound possibilities PoyoPoyo put into my head led me directly to ask Jonathan Kirk to write a piece for horn and electronics. In our initial meetings, I demonstrated some possibilities of the harmon mute, and he ended up using it in his piece Nine Mile Canyon, to my delight. Besides being a wonderful and inventive composer, Jonathon performs and improvises on brass instruments and electronics, and I knew to expect something awesome. I was not disappointed. The piece starts out pitchless, just taps and whispers, wind blowing through and around rocks and brush. But later, when the acoustic horn is augmented and heightened by echoes and distortions, the sound density is nearly overwhelming. This is a unique sound world Jonathon has created, and in some ways the opposite to Fujikura's. PoyoPoyo is never assertive. It is always asking questions but not really waiting around for the answers, bouncing along to the next question. In contrast, Nine Mile Canyon is bold, a real 'outdoors piece' (appropriate for the horn, originally an outdoor instrument). It demands attention in its quietest and its loudest moments.

I'm relating all this because, in many ways, Nine Mile Canyon is the catalyst for the program happening on Oct 18 at Constellation. And I say 'program' very consciously. While in many ways I could call this performance a 'recital', that doesn't feel right. Jonathon and I premiered the piece this summer (as part of the ambitious Omaha Under the Radar festival) at a bar, and while that setting wasn't ideal, it certainly felt more appropriate than a concert hall. The conventions of a recital – perform a piece, bow, leave the stage, return, perform a piece, bow, leave, take an intermission, repeat – are unnecessary here, and are being dispensed with.

The four pieces on the program (which will also include Stockhausen's In Freundschaft for solo horn, and Grisey's Accords Perdu for two horns) will be performed without interruption as a single set, with connecting material mostly provided by Jonathon's electronics set-up. I won't be wandering on and off stage, breaking the mood between each piece. The audience will be taken from one unique sound world directly to the next, hopefully discovering relationships between the pieces that will only unfold in the moment.

My social media account just reminded me that I received PoyoPoyo in the mail, with a handwritten note from Dai Fujikua, one year ago today. It's taken a year, but the set of circumstances has culminated in what will certainly be a unique experience!

Dal Niente Presents: Matthew Oliphant

Sunday, October 18, 2015, 8:30pm

Constellation Chicago

3111 N. Western Avenue

$15 General Admission/$10 Students

To purchase tickets for Dal Niente Presents: Matthew Oliphant,

click here!

Youth In New Music

Dal Niente guitarist Jesse Langen describes his experience with youth new music ensembles from Germany and Chicago. This extraordinary collaboration culminates on October 16, 2015 at the first-ever International Youth New Music Festival in Chicago.

Dal Niente guitarist Jesse Langen describes his experience with youth new music ensembles from Germany and Chicago. This extraordinary collaboration culminates on October 16, 2015 at the first-ever International Youth New Music Festival in Chicago.

Studio Musikfabrik performed at Darmstadt 2012, and all of us who were there felt that their concert was as good as the concerts by professional ensembles that we’d been hearing all week. Obviously it was a revelation to hear teenagers playing at this level, and we all came home full of ideas and energy. Over the course of the next couple of years I organized my students into a new music ensemble, and we commissioned pieces that year from a number of Chicago composers. In the summer of 2013 Thomas Osterdiekhoff, the director of Ensemble Musikfabrik, visited Chicago and heard a recital my students gave. They had been studying with Fred and Morgan, and Thomas heard my students play pieces by these professional composers next to pieces my students wrote that came from coachings with those composers. He was impressed enough to propose a collaboration between Studio Musikfabrik and my students.

I was simultaneously ecstatic and terrified. The way I saw it at the time, what my students had going for them was a relatively high level of composing skill, sensibility, and experience, and performance instincts shaped by these strengths. What they didn’t have was technique on their instruments anywhere near those of Studio Musikfabrik, who are all essentially professional level players.

At the same time, I think Thomas understood for the first time what my students actually are. For the year leading up to that summer concert, Thomas and Peter Veale would occasionally ask questions like “Are your students composers or performers? Or do you have two sets of students?” The educational system in Germany is very different from ours; they focus earlier. It was foreign enough for them that I had a group of students who composed for themselves that it took a year of emails and a visit for that picture to make sense.

Our tendency with talented kids is to encourage them to do everything; so the first chair violin will also be a composer, and play guitar in a band after school, and play in the jazz combo, etc. This tendency showed in an evolution in my youth ensemble; the kids went from playing commissions to writing pieces for themselves to writing collaboratively. The collaborative writing started within a year, and it was new territory for me and for all of the coaches I hired. More than once I got questions from my American colleagues like, “if no one is composing the piece, who is supposed to get credit for writing the piece? Who is responsible? Whose vision are they supposed to be executing?” And I didn’t know how to answer these questions, to my wonder and embarrassment. After all, this is supposed to be my field, both as a teacher and as a player; but more and more I would show up to my students’ rehearsals knowing that I had no idea what was going to happen. These kids were becoming a super-mind that I couldn’t always keep up with.

In November 2013 I went to a youth new music ensemble festival in Berlin. Germany has many youth new music ensembles, and there was a day of concerts of ensembles from all over the country. Seeing all of these ensembles, I had a two-part revelation. First, every one of the kids I heard played at a higher level of technical proficiency on their instruments than my students. Second, none of these ensembles did anything like what my students did; they exclusively played pieces by professional composers. By this time, my kids were more like a rock band than like any equivalent in classical music or new music.

At dinner that evening, we discussed the event and all of the performances. I expressed my perspective on how my ensemble fit into the picture (with some trepidation!), and happily the feeling across the table was one of enthusiasm. My ensemble does something that none of the other ensembles do. It’s hard to imagine a youth new music ensemble, modeled after a normal adult ensemble, contributing to Studio Musikfabrik’s experience, as they are simply the best youth new music ensemble of that sort in the world. However, what my ensemble does may not have any equivalent at all, educational or professional. We have something to contribute.

In my wildest dreams, the way these kids work will shift the ground in my field, or create new ground, where a number of players who were educated by learning to compose, perform, improvise, and collaborate simply continue doing all of that into their adulthood, and find ways to generate audiences and get paid. At my most enthusiastic moments I allow myself to imagine that my students will make a new new music, or that they are already doing that.

The concert next Friday night at DePaul will have four parts: Ensemble 20+, Studio Musikfabrik, Chicago Arts Initiative Ensemble, and a collaborative concert with Studio Musikfabrik and Chicago Arts Initiative. The collaborative concert will involve creative contributions from Studio Musikfabrik, both in material they’ve sent us and throughout our rehearsal process next week. I can say that this is the most important thing that I’ve done, and I believe it will be an important night for education and for music.

A number of people and institutions have been instrumental in all of this. The students in the ensemble are all either current or graduated students of Chicago Academy for the Arts. Monica George, executive director of Chicago Arts Initiative and a true visionary, has made this project conceivable on the American end. There is no doubt in my mind that Monica will change the world for the better, starting with this project. It probably comes as no surprise that Ensemble Dal Niente is deeply involved in a number of ways. Reba Cafarelli, Dal Niente’s executive director has been immensely enthusiastic, supportive, and full of indispensable help. Michael Lewanski has worked with all of my students for years, knows my teaching inside and out, and has facilitated this project in particular in more ways than I could count. DePaul University opened their doors to this project without hesitation, and have gone to great lengths to help us with a variety of elements of the project. Irmi Maunu-Kocian from the Chicago Goethe Institut has been working with me on this idea for more than a year; I’d go as far as to say that many of the good ideas and clear thoughts in this project have been hers.

Finally, a number of composers and performers deserve mention with this project as coaches who have shaped both my own teaching and the culture of my students. Jenna Lyle worked with the students extensively last summer, and upped every aspect of our game. Rachel Brown has had that role this summer, and walked in the door the first day seeming to already understand everything we were doing. Fred Gifford has worked with the kids many times over the years, and his ideas are in the room with us all the time; he will eventually run into a teenager he’s never met who can explain “timbre wheel” and other unique ideas of his to him. Eliza Brown, Chris Fisher-Lochhead, Morgan Krauss, Ray Evanoff, Marcos Balter, and Pablo Chin have all had a significant impact on this ensemble. Amanda DeBoer Bartlett has coached my students extensively to our great benefit, and Quince, both as an ensemble and as individuals, has been instrumental. Among the many Dal Niente players I owe thanks to I would mention Mabel Kwan in particular, who has probably been involved in the majority of my students’ creative activities.

-- Jesse Langen, Ensemble Dal Niente Guitarist

International Youth New Music Festival

Friday, October 16, 2015

8:00 PM

DePaul University Concert Hall

802 W. Belden Avenue

ADMISSION FREE

Canciones

Michael Lewanski talks about the program on Dal Niente's 10th Anniversary Season Opener on Sunday, September 20 at 2pm at the Harold Washington Library.

On “Latin American” music

To speak about Latin American music probably makes about as much sense as to speak of North American music. Which is to say, it is immediately apparent that the term is of limited usefulness: all that can be definitively made is a claim about geography (and it is immediately apparent that this is not particularly definitive; how does one characterize the music of a composer born in one location and living in another, as many on this program are?). My limited, unscientific, anecdotal experiences in Mexico, Colombia, and Panama on tour with Ensemble Dal Niente in June 2015 (having been to each of those countries once before) suggested to me that the only generalization about Latin American music was that a generalization was impossible. Yet, rightly or wrong, one makes an attempt to generalize; the geographies, political situations, and languages of Latin and North America are different; surely culture reflects this. Just as an attempt to make a generalizable distinction appears, though, it collapses. North America and Latin America also share a word in their names, a landmass, time zones, a history rooted in conquest, colonialism, violence; an argument could be mounted that these cultures have more in common, than, say the US and Europe. Hesitatingly, I ask: might it make more sense to simply speak of an “American music” in the broadest sense? But for now: let us attempt to live in these contradictory thoughts.

A trend I provisionally perceived in the works that Ensemble Dal Niente took on its tour involved what seemed to me to be an unmistakeable willingness to write about political situations. But the way in which this is manifested in each work is very different; and none of them are facile or seem to make naive claims about their direct efficacy in, say, an electoral arena. I’ll talk about three that appear on our 10th anniversary season-opening program, Canciones.

Regarding his work verdaderos negativos ("real negatives"), Colombian composer Rodolfo Acosta writes the following:

Its title refers to the deplorable phenomenon of so-called "false positives", especially in its most tragic use: the killing of civilians by military forces in order to prove the latter's supposed effectiveness. In the most recent Colombian case, these crimes have been perpetrated in order to make the victims pass as guerrilla combatants killed in battle. Unfortunately, this is not a recent practice, nor is it exclusive to the Colombian Armed Forces, as is witnessed by other societies in Latin America and in the world generally. On the other hand, although the term refers to "presenting the false positive results" of a military institution (and the killing of innocent people is not the only kind), we cannot lose sight of the fact that considering a person's violent death as something "positive" is grotesquely inhumane.

Thus, its concept and title is a play on opposites: the false is the radically real; the positive is the negative. Musically there are, similarly, contradictory forces at work that create an experience for an audience of unusual directness. On one end are the drumkit and bass parts, whose rhythms are rigidly notated. They can be read as representing the forces of a violently aggressive way of organizing time (along the lines of what a military force or tyrannical government might do); but also, simultaneously, as a reference to popular music styles that can be themselves seen as both resistant and compliant. The melodic parts (the work is for an open instrumentation, requiring the performers to choose) are notated permissively, with suggestions for thematic contours and instructions like “fluctuating dynamics.” They force the listener to consider individual voices, and force the players to be individualized – the opposite of what governmental forces do in killing civilians and passing them off as guerillas. Which is to say, the action of creating “false positives” is an attempted erasure of the individual on multiple levels – in the act of murder, and that of attributing to the victim an identity that is not theirs. The melodic sections of the piece make it so that the players (both as musicians and human beings) do the opposite. They must thematize their own particularity, such that their musical effort goes into being not together; and they must also make choices regarding their specific life circumstances, i.e., what instrument they're playing. Yet on top of these layers of meaning, the overall affect is one of a certain unified rage (on the part of the musicians and composer and, hopefully, the engaged audience) against injustice – a visceral feeling of disgust and anger.

On the opposite end of the affective spectrum is Francisco Castillo Trigueros’s Geografias. According to the composer, in the work

several poetic and musical visions of Mexico coexist. The text, constructed from symbolic and narrative fragments, builds a dramatic arch, illustrating different facets of the natural, cultural, political, and mystical geography of the country, from a distant and semi-nostalgic perspective.

The music is understated, its unflappable character often of a mimetic nature that masks an underlying subtlety and sophistication. We are introduced to a narrative subject, one that surveys the landscape. As the music gradually moves on, with an epic patience, it becomes increasingly clear that this is not an ordinary narrative subject. Phrases like “the heavy air was burying my body into the humid earth,” and “my pulverized bones crunching under its pressure” give us clues that the fate of the narrator is not a happy one. As the work develops, the status of all elements become increasingly blurred – are the piece’s sounds natural or musical or in a fluid state between those two? Is the narrator asleep or awake or alive or dead or does s/he even know? Is the genre an accompanied narration or an art song or both? In the end, we know the whole time that something has happened to this narrator, an event, an occurrence, a trauma. The question remains for us until the end: what is it?

On our program Canciones (“Songs”) perhaps the most clearly “sung” is Federico Garcia-de Castro’s Memoria. The composer writes that

[t]he idea for [the work] stems from the last 3 things that Bernardo Jaramillo Ossa, then presidential candidate for the Colombian left-wing party Unión Patriótica, said to his wife while dying in her arms after being shot in the Bogota airport in 1990: "Sweetheart, I can't feel my legs;" "Those assholes just killed me;" "I am dying, embrace me, protect me."

“High culture” art songs have a long, complicated history; when the so-called classical music lover recalls it, perhaps Schubert comes to mind first. Easily passed over (but maybe quickly remembered) is how much sense his works made in his culture: so much so that the phenomenon of Schubertiades, essentially, listening parties for Schubert’s songs, were common events in the Vienna of his day. It’s tempting to forget that Schubert wasn’t setting the poetry of Heine, Goethe, Schiller, Müller because they were “canonic” figures but rather because they were the widely read poets of his day. Returning to the work in question: while the words spoken by a dying man were assuredly not intended to be poetry, it requires but a few conceptual leaps to see the setting thereof in an art song as part of a tradition of topicality. Or one might view it ironically – whereas German 19th century poetry is highly refined, nothing could be more spontaneously uttered than a person directly confronting their own mortality. Regardless, both Schubert’s and Federico’s contemporaneous audience are the best interpreters of their music. To put it another way: the impact of a musical setting of the words of a public figure relatively recently assassinated, from a country with a history of a fraught political relationship with our own, is likely to impact us in a unique way.

The musically conservative elements of Memoria emphasize a certain radicality. It contains an acoustic guitar cadenza that could fit right into Rodrigo’s Concierto de Aranjuez; its harmonic language relies heavily on open intervals and triads; its music contains conventional reflections of the semantic content of the text. Yet at the same time, the instrumentalists break out of their traditional role as simple accompanists. They come across as (because they are) human beings who comment, respond, exhort, complain; they envelope the lonely soprano in whirlwind of whispered secrets while she meditates on fundamental questions of human existence.

In closing, I wonder this: will an audience find its conception of what it considers “American” music changed as a result of these encounters with “Latin American” music? I’m interested to find out, and I certainly invite your opinions.

-- Michael Lewanski, Conductor

Ensemble Dal Niente

10th Latino Music Festival Presents

Dal Niente’s 10th Anniversary Season Opener:

Canciones

Sunday, September 20, 2015

2:00 PM

Cindy Pritzker Auditorium, Harold Washington Library

FREE Admission

Why cat videos are awesome: New Music, Score Follower, and YouTube

Dal Niente conductor, Michael Lewanski, shares some thoughts on an upcoming commissioning project with Score Follower/Incipitsify.

Why cat videos are awesome: New Music, Score Follower, and YouTube

by Michael Lewanski

The history of music is also the history of the circumstances of its production.

This statement, I add hastily, is not meant to take anything away a from a l'art pour l'art (that is, “art for art’s sake”) way of talking about or interpreting music (one which focuses on its intrinsic value or asserts that it is its own justification, separated from how it came to be) -- such an approach has numerous and obvious benefits in terms of understanding how music does what it does.

It’s just that it seems to me that a tacit, unthought ethos of “art for art’s sake” unconsciously underlies a vast majority of our cultural conversations about music among musicians and audiences alike. Musicians do this all the time: at its best and most sympathetic, they pay attention to a work's form or harmony according to guidelines they learned in school. Or perhaps they evaluate the professional skill of performers during a concert. I would even argue that musicians in a rehearsal complaining that a piece is not well-written for their instrument, or saying that they like playing new music but don't like listening to it are extensions of this basic attitude. And concert-goers regularly make some version of these statements: “I just like the way it sounds” or “I don’t understand it but I like it." Paraphrasing Dahlhaus, even the habit of not paying attention to the meaning of the words of Schubert songs is the same basic attitude. (And it may often mask an economic-ideological function, following Marx -- music as a thing for relaxation, something to help you take a break and not think too hard… in short, a commodity, a sit-com, a piece of furniture, that by its nature as photographic negative, reinforces the system that makes commodities possible. Don’t think it’s coincidental or accidental that Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer has “ars gratia artis” when the lion roars at the beginning of their movies.)

Anyway, I don’t want to get hung up on that, because there are good sit-coms and nice furniture in the world; and, like I said, there’s a lot of merit to a l’art pour l’art approach. I want to claim, simply, that it’s not the only approach; the problem for me is that it is tacitly prioritized over many others. A more realistic interpretative stance, it seems to me, is one in which we attempt to hold contradictory frameworks in our head simultaneously.

Let me, therefore, make some broad assertions about other ways of thinking.

Lots of music, for a very long time in European history, was written (by which I mean both “composed” and “written down”) for performance in church. The church had a particular use for music, thus enabling its development from plainchant to organum to polyphony over the course of many centuries. Which is say, something about its use-in-church-ness ends up defining the way it sounds, what form it takes (masses, motets), its musical architecture (church modes and their descendants), its instrumentation (rather, that it tends to be for voices), and the circumstances of its performance.

The Enlightenment, and the development of 19th century industry, brings along with it various notions of bourgeois freedom and self-determination. People can pay for stuff. "Those that had some leftover wealth want, not only to pay for stuff, but also to show that they can pay for stuff, because flaunting their wealth is a sign of their status." It seems sensical that an industry would develop to allow the middle class to affordably have music in their households, in their chambers… so we get “chamber music.” Such a setting also enables an intimacy that other venues might not allow; that, in turn, enables the rise of connoisseurship, as well as a trend in chamber music for compositions to be more affectively complex than the public statements of symphonic music.

While one might argue that pop songs are three minutes long because of shortened attention spans, it seems to me that an equally plausible argument is that it has something to do with the fact that 78 RPM records last three to five minutes. (Not that these arguments are mutually exclusive; it’s just that it’s easy to blame kids these days and to forgot that making those kids how they are these days may have been a calculated decision and had a particular mass-produced, real-world object associated with it.)

All of the above paints with a very broad brush and without much nuance. But while the precise details of these historical claims can be debated, it would be hard to question a basic, general premise: the historical, on the ground, nitty-gritty, stuff-in-the-world, accidental-thingy-ness aspects of musical production are deeply related to the content of the music itself -- its form, its timbre, its affect, etc. As Jacques Attali (in Noise: The Political Economy of Music) put it, more specifically about instruments themselves, “Beethoven’s Sonata no. [sic] 106, the first piece written for piano, would have been unthinkable on any other instrument. Likewise, the work of Jimmy [also sic] Hendrix is meaningless without the electric guitar, the use of which he perfected.” (I like this juxtaposition of “high” and “low” culture because it accords with a subtext of this essay.)

I don’t mean to suggest that this stuff-in-the-world quality of music is a detraction. If anything, it’s the opposite, because it means music is always related intimately to life. (Tangentially, there is so much hand-wringing in professional music performance circles about new music and its “accessibility” that I just can’t figure out. What could be more accessible than the stuff being made in the world by your fellow humans? But also: why do we expect that new pieces must be instantaneously fully comprehensible? Nothing else in your life is, from the behavior of your co-workers, to the stuff your mom says, to why this stoplight is so long, to why you did that dumb thing last week that surprised even you.)

And so, here we are in 2015. We at Ensemble Dal Niente were approached by the team behind Score Follower/Incipitsify, an organization that “makes recordings+score videos of modern compositions and posts them to their YouTube channels.” They wanted to commission a new piece of music. When I first heard about this, it seemed incredibly bizarre and unlikely -- a YouTube channel wanting to commission a piece of music. YouTube is hardly 10 years old, and it is full of cats doing cute thing, too-much-information confessionary videos, commercial music, highlight reels of athletes, all six Star Wars movies playing at once, family vacations shot on iPhones, grainy academic lectures, Mozart vs. Skrillex, high school orchestra concerts, cartoons, and people going Super Saiyan; in short, the strangest, most beyond-imagination collection of diverse, life-affirming weirdness that human culture has ever created. But this is why a SF/InciP commission makes so much sense -- because that is exactly our experience of life in 2015, and it seems a trend unlikely to go in the opposite direction (assuming, as I should not, that a cataclysmically violent political-military disaster won’t occur).

Something in US culture today allows an organization to arise that wants “to provide access to a type of experience (viewing a score while listening to the recording) only otherwise available to the privileged (students/faculty who happen to be affiliated with a university that has a large catalogue of new music scores).” Of course, one might argue that the very ability to read a score is itself privileged. One would not be wrong. However, let us not use the political history of cultural institutions to hamstring the future. The recent history of (much but not all) new music, is, as SF/InciP’s website hints, a history of privileged people having access to things that are privileged in multiple sense: the (physical) location (of their performances and notated materials) in a fancy university/concert hall, the hermetic code of their notation, even the language and style of their discourse (omg, and isn’t “discourse” such a word that would appear in such discourse). Ironic for a field with so many Marxists, new music for so long had such reified character -- where it came across to an outsider as a thing, an already-fully-formed impenetrable and uninterpretable object, profoundly unrelated to the world that made it and to the circumstances of its production.

In a world full of increasingly more humans, ever-more-rapidly-developing technology, and ever-less trustworthy institutions, it only makes sense that a complex, long-developing, multi-step process of putting “modern compositions” -- or, to use a term that is no less problematic because of the seeming simple claims it makes, “new music” -- out there to be listened to, looked at, demystified, misread weakly or strongly, accords with the character of current social development. From a strictly personal point of view, I’m super excited to be the conductor of an organization that would embrace such a project.

To take it a step further, this process of “putting stuff out there” changes the character of the art that is made; it becomes part of the circumstances of the production of music. I’ll take a risk and offer a bold prediction -- one of the sort that can be empirically proved wrong (making me look like a idiot) in September 2016, when we play the new piece. A characteristic of the winning work will be such that it could only have been conceived, following Attali, because it was commissioned by a YouTube channel. Its online-media-ness will somehow, in some way I don’t yet know, be thematized and audibly/visually? instantiated in the work’s form and/or character and/or materials and/or whatever. It won’t just be a piece that simply says “I’m a regular old concert piece” because, first of all, there are no such pieces and it is ideological to think there are; and secondly, because it will have been conceived under circumstances that precludes such an artistic statement. I can’t wait to hear and see what that is.

Visit Score Follower/Incipitsify's Indiegogo Campaign here to read more about this commissioning project and to make a donation!

Apply for a Dal Niente Internship

Find out how you can join the Dal Niente team for the upcoming 10th Anniversary season.

Dal Niente is hiring interns for the upcoming 2015-2016 season. This is a unique opportunity to gain valuable operations experience with a leading new music organization.

Key responsibilities include:

- Update the Chicago venue research project (intern would physically visit venues in order to deepen the Dal Niente relationship)

- Assist with social media, marketing, and PR strategic development

- Assist in the organization and design of concert programs and other concert materials

- Maintain the donor database

- Help order and manage the library / score database

- Archive past projects

- Assist on-site at Chicago-based Dal Niente concerts and events throughout the season with possible tasks including but not limited to:

- Assist Operations Director with preparations for concerts in the weeks leading up to the event

- Provide on-site manual assistance for load-in, set up, and stage changes

- Staff marketing table at events: sell Dal Niente merchandise, facilitate the dissemination of marketing materials, facilitate email list signups and audience surveys, answer inquiries from patrons, etc.

Requirements:

The ideal candidate for this position is driven, self-motivated, able to work independently, willing to follow direction, works well as part of a team, and detail oriented. The intern will have strong multi-tasking skills; music knowledge; understanding of Google Docs, Google Drive and Gmail; be Social Media savvy; have the ability to follow-through on large projects; and has their own laptop computer in working condition.

To Apply:

Applicants must submit a cover letter and 1-2 page resume listing all relevant experience with the creation and presentation of music, arts administration skills, and leadership roles. Email materials to Kayleigh Butcher at kayleigh@dalniente.com.

Hasco Duo Set to Kick Off Dal Niente Presents Series

Whether improvising or playing a piece based on the rules from Magic the Gathering, Hasco Duo explores exciting and unusual sound worlds. Check out this brief interview to learn more about the duo and their upcoming Dal Niente Presents concert.

(Photo: Aleksandr Karjaka)

Soprano Amanda DeBoer Bartlett and guitarist Jesse Langen joined forces in 2013 to form Hasco Duo, and have been commissioning, performing, and recording at a breakneck speed ever since. As part of Dal Niente’s 10th Anniversary Season, Hasco Duo will perform twice this Fall- first representing Dal Niente at the New Music Chicago 10th Anniversary Birthday Bash on September 11, and in a full length Dal Niente Presents program on September 14 at The Hideout.

We asked Amanda a few questions about the ensemble’s history and a preview of what to expect on September 14:

Q: How long has Hasco Duo been together? What was the inspiration that led you to form the ensemble?

A: Our first duo show was a Dal Niente Presents show at the Empty Bottle May 2013, which was part of a series called (Un)Familiar music run by Doyle Armbrust. It was originally supposed to be a solo show for Jesse, but after working together on Aaron Einbond's Without Words, we decided to collaborate. We commissioned 7 new pieces for the show; it was quite an undertaking! After that, we played shows together sporadically in Chicago and Omaha, but it wasn't until we put together our first improvised show at the Experimental Sound Studio in the Fall of 2014 that we came up with the name - a respelling of the word chaos - and started recording our first album.

Q: How many new works has Hasco Duo commissioned or premiered? What's your approach to programming a concert that features both older and brand new works?

A: Our approach to programming is very intuitive and impulsive. Half of our output is improvised, and we're always devising new schemes and material on our own or with collaborators. We've also commissioned music from Marcos Balter, Eliza Brown, Ray Evanoff, Fred Gifford, Morgan Krauss, Max Grafe, Jonn Sokol, Ravi Kittappa, and Chris Fisher-Lochhead. We haven't played much older music, although Jesse made some pretty stellar arrangements of DuFay songs for the Mathias Spahlinger festival "there is no repetition" back in March.

Q: What have been some of your most memorable past performances?

A: Our first show as Hasco Duo at the Experimental Sound Studio last Fall was very formative. It was our first improvised show, and we honestly didn't know if it would work. We sort of shot in the dark during the whole process, which was exciting. For that show, we mixed in some of our commissions alongside improvisation and tried to create a narrative for the material. During one piece, I was just laughing the entire time and Jesse was trying to do something very serious. The combination was a little absurd, and the audience was laughing along with me. I remember loving that moment and feeling like we had accomplished something since people were reacting to the performance. I loved that people felt comfortable enough to laugh along with us.

Q: Tell us about your upcoming program on 9/14 at the Hideout. What are some things that audiences can look forward to?

A: We've commissioned new pieces from Ray Evanoff, Morgan Krauss, Max Grafe, and Jonn Sokol for the show, and will be interspersing our own work in the mix. Ray's music is very active and demanding, layering complicated vocal and guitar techniques to create completely novel textures and sounds. Morgan's music, like Ray's, can be very physically demanding, but she creates worlds of repetition with subtle perturbation and fluctuation. Jonn Sokol's piece uses rules from the Magic the Gathering card game and text from one of my favorite books, The Prairie and the Sea by William Quayle. I'm not sure a piece has ever been written more suitably to Hasco's interests! And finally, Max collaborated with a poet friend to create a piece which takes the perspective of the first Mars colonizers.

I absolutely love this program! All of the composers involved are long-time friends and collaborators, and it really shows in the pieces they created. Morgan and Ray were both part of our first project at the Empty Bottle, so it's very meaningful to work with them again as the ensemble continues to develop. Max and Jonn's music is so beautiful, and I want to hear more of it performed in Chicago.

Don’t miss Hasco Duo at The Hideout on September 14 at 8:00 PM.

10th Anniversary Season Preview

Throughout the 2015/2016 Season, Dal Niente will celebrate the repertoire, composers, and musicians that have contributed to the ensemble’s extraordinary array of accomplishments, while forging ahead into the next decade and beyond.

Ensemble Dal Niente proudly announces its 10th Anniversary Concert Season in 2015/2016. Over the past decade, Dal Niente has established itself as Chicago’s most prolific presenter of contemporary classical music by commissioning and premiering hundreds of new works and pursuing innovative collaborations. Throughout the 2015/2016 Season, Dal Niente will celebrate the repertoire, composers, and musicians that have contributed to the ensemble’s extraordinary array of accomplishments, while forging ahead into the next decade and beyond. Conductor and Artistic Coordinator Michael Lewanski says, "Dal Niente's 10th Anniversary Season invites listeners to engage with and interpret the huge variety of music being created in our enormous and contradictory world; and to discover how that music is a product of, a commentary on, and a necessity for our lives and our society."

The 10th Anniversary Season Opener takes place on September 20 at the Cindy Pritzker Auditorium of the Harold Washington Library with Canciones – the culmination of Dal Niente’s Latin American tour to Mexico, Colombia, and Panama in June 2015 made possible by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation’s International Connections Fund. Presented in partnership with the Latino Music Festival, this admission-free performance features the U.S. and Chicago premieres of six stylistically and thematically diverse pieces by some of Central and South America’s most compelling contemporary composers. Listeners are invited to learn more about the ensemble’s cultural exchange with Latin America’s new music communities through a multimedia presentation and panel discussion with musicians and composers from the tour.

Since its founding, Ensemble Dal Niente has regularly introduced Chicago audiences to the most thought-provoking work being written today by German composers. This tradition continues when Dal Niente kicks off its Neue Musik tour, made possible by the generous support of the Ernst von Siemens Musikstiftung, at Chicago’s Constellation on December 6 followed by repeat performances in Boston and New York City. This program explores German musical culture as it re-thinks, re-invents, and re-works itself and its relationship to today’s complex world.

The 2016 Frequency Festival will celebrate the invaluable contributions of Constellation to Chicago’s new music scene. As part of the Festival on February 28, Dal Niente will revive its much-loved Hard Music, Hard Liquor series, this time with a thrilling chaser of ensemble works by the iconic Chicago-born composer, George Lewis. A spectacular display of impossibly virtuosic, mind-bending solo works will push Dal Niente musicians to the very limits of their abilities, followed by two ensemble pieces – Hexis and Mnemosis, in which “it is the listener who improvises rather than the performers” – by the inimitable Lewis, one of Dal Niente’s most treasured collaborators.

Party 2016 on April 30 will be an epic, not-to-be-missed affair - a fitting fête for Ensemble Dal Niente’s 10th Anniversary Season. In what has become Dal Niente’s signature event, The Party encourages listeners to sit, stand, lie down, drink, eat, and connect with fellow audience members while experiencing a marathon of riveting live performances. This year’s Party will be set against the cavernous backdrop of Mana Contemporary in Pilsen, with the collaboration of Chicago’s cassette-tape label and performance art collective Parlour Tapes+, who will compose a new work for the occasion. Stefan Prins’ Generation Kill, featuring live video, electronics, and video game controllers, is one of the most ambitious works that Dal Niente has ever tackled. The Chicago premiere of Deerhoof Chamber Variations by Greg Saunier will also mark the release of a new album on New Amsterdam Records featuring Dal Niente, indie-noise band Deerhoof and composer Marcos Balter. A portrait album of Mikel Kuehn on New Focus Recordings will also be released, alongside the world premieres of works by Natacha Diels, and Dal Niente’s founding Executive Director Kirsten Broberg. Captivating performances, sumptuous snacks, delectable libations, and an eclectic audience will make for an evening not soon to be forgotten.

Over the course of the season, Ensemble Dal Niente will continue its popular Dal Niente Presents series, which showcases the extraordinary artistic strength of its ensemble members in self-curated solo and chamber music programs. A stirring performance and album release featuring Hasco Duo – Amanda DeBoer Bartlett (soprano) and Jesse Langen (guitar) – marks Dal Niente’s first-ever appearance at The Hideout on September 14. Hornist Matthew Oliphant will push the sonic possibilities of his instrument with a solo recital at Constellation on October 18. The virtuosic and versatile pianist Mabel Kwan will perform works from her new solo album at Constellation on January 3. Harpist Ben Melsky and guitarist Jesse Langen will offer an exciting program of all-new works for this largely unexplored instrumental combination at Elastic Arts in Logan Square on January 23. Finally, Dal Niente highlights two of its newest ensemble members at Constellation – flutist Emma Hospelhorn and clarinetist Katie Schoepflin – showing off the adventurous sides of their instruments on March 6.

Increasingly in demand across the country for its bold performances and in-depth residency work, Ensemble Dal Niente will visit the International Computer Music Conference at the University of North Texas (Denton, TX), the School of Music at University of Washington (Seattle, WA), NUNC! 2 at the Bienen School of Music at Northwestern University (Evanston, IL), Boston University (Boston, MA), the Permutations series at the DiMenna Center (New York, NY), Western Michigan University’s School of Music (Kalamazoo, MI), and June in Buffalo hosted by the Center for 21st Century Music at The University at Buffalo (Buffalo, NY).