By Michael Lewanski, conductor

Serenade, the 19th of the 21 songs of Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire (actually, the composer calls them “melodramas”—which, upon reflection, totally feels accurate, even given their miniature size) is even more meta-musical than the others. (And that is really saying something. Pierrot has got to be one of the most desperately self-conscious pieces in historical music, making heavy-handed use of a dizzying number of past genres and composers: Chopin (explicitly named in a title), the waltz, the menuet, the passacaglia, the barcarolle, the rondo, all manner of Baroque counterpoint, a bunch of others I can’t keep track of because of aforementioned dizzyingness). Anyway here’s the text of Serenade, in my own not very good translation because I don’t really speak German:

With a grotesquely outsized bow

Pierrot scrapes on his viola,

Like a stork on one leg,

Sadly he plucks a pizzicato.

Suddenly Cassander’s here—frenzied

by the nighttime virtuoso—

With a grotesquely outsized bow

Pierrot scrapes on his viola.

Now he throws aside the viola:

With his delicate left hand—

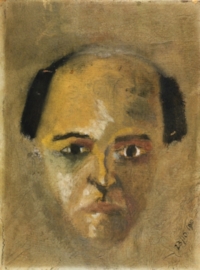

He seizes the bald man by the collar

Dreamily he plays on the bald spot

With a grotesquely outsized bow.

On the one hand, this is an eccentric, kinda creepy, actually-a-bit gross fantasy, the sort of thing that shows up randomly in your dreams between an appearance of your long-dead first pet and your cisgender, heteronormative, right-wing uncles dressed in matching drag singing a song from Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory. Less weirdly and more generally, another way to construe it is as a description of the project of new music at its best, though I hasten to add that we definitely don’t always live up to it. I know you’re skeptical but stay with me: in what we do, as new music people, something unexpected might happen to an instrument, or to a sound, or to a genre; this thing might be disruptive, causing you metaphorically (or literally) to stay awake at night; when you try to interrupt us, though, rather than stop, we make you the instrument. Put another way: when we do things right, new music is an art form that bows your bald spot. It does funny things to how your head feels.

Like I said, we don’t always live up to it; more often than not we don’t. Life is tough under Trumpian nepo-capitalism, where some people's nauseatingly rich family members and friends get more nauseatingly rich and more, well, straight-up nauseating; and everyone else is srsly just trynna make a buck. Thus, it’s easy for new music to just, like, play music, cross our fingers, look pretty, smile wide, and hope y’all like us [gritted teeth emoji].

“[I]n what we do, as new music people, something unexpected might happen to an instrument, or to a sound, or to a genre; this thing might be disruptive, causing you metaphorically (or literally) to stay awake at night; when you try to interrupt us, though, rather than stop, we make you the instrument.”

But, as a project by a new music ensemble, it’s nice for Dal Niente’s STAGED series to remember the example of Pierrot Lunaire. Of course, Pierrot is SO not new music; it was written in 1912, before World War I, in a world hopelessly smaller, whiter, more patriarchal, and more racist than our own. (Yeah, tbh, maybe not more racist.) But on the other hand, Pierrot is SO new music; if anything, it’s new music’s prototypical work, and a self-consciously prickly one. There are some obvious details: here’s a boring history lesson about blah blah blah one-of-the-earliest-examples-of-free-atonality, whatever; there are IMPORTANT INNOVATIVE IMPORTANT uses of instrumental important techniques that are innovative and important [eyerolling emoji]; and last but certainly least: the typical new music instrumentation (violin, cello, piano, clarinet, flute) is named after it (“Pierrot plus percussion” comes out of a new music person’s mouth about as much as “accessible” or “impactful” or “post-minimalist” or “why didn’t we get that grant” does). But gosh, it’s so much more and so much better than IMPORTANT AND INNOVATIVE early examples of free atonality. It, like, doesn’t, like, always sound good. It’s uncomfortable. It’s tortured. It makes directly contradictory claims about its status. For instance: what’s the deal with that idiosyncratic singing? Is it actually singing? What is singing anyway? Worth remembering: it was commissioned by a person (Albertine Zehme) who was not actually a professional musician or singer, but an actress. The sprechgesang (spoken-sung) or (more commonly) sprechstimme (spoken-voice) style of the vocal part is simultaneously alienating and familiarizing. It’s more natural than classical singing (which, let’s be honest, is zero percent natural), but also is not imitative of everyday speech either. You might feel yourself drawn to sprechstimme at the same time that you find it repulsive or abject. It somehow recapitulates what you do when you speak, but it’s much more wretched and intimate and violent and embarrassing—it’s the id to your everyday language’s ego.

Speaking of dilettante pscychoanalysis, maybe what I want to really say is that Pierrot Lunaire is the id and the superego in the same piece. (It would be difficult to imagine that Schoenberg wasn’t influenced (even if—wait for it—unconsciously (see what I did there?) by Freud’s ideas, which were floating around early 20th century Vienna). It performs more than its share of strange, terrifying, for realz bizarre, free-associative fantasies: decapitation by the moon, ginormous moths that blot out the sun, smoking in a person’s skull, returning to a long-absent-from home (one that, hmmmm, actually you’re not quite sure you’ve ever been to now that you really think about it wait was my childhood real actually did any of us actually have childhoods wait are still all children whoa). But at the same time, it wears the rigor of its organization on its sleeve as so much a point of pride that it feels defensive and trying-too-hard: it is the composer’s Op. 21, and it’s 21 songs, begun on March 12, 1912; but it’s not just 21 songs, it’s “Three times Seven Poems” (according to the title); seven-note motifs are used throughout the work, including the famous piano opening; there are seven musicians that perform. Pierrot Lunaire overly insistently promises you, sugarily, that your listening experience is structured.

Maybe I’m skipping a step here, but I feel like Pierrot Lunaire is the perfect work for a new music ensemble’s series about the stage not because of its IMPORTANT INNOVATIVE IMPORTANCE OF INNOVATION, but because it masterfully performs the therapeutic functions that are the reason we go to the theater, and it does so in a way that is fundamentally musical. It is both hyper-real and deeply fake. It mirrors your contradictory experience of existence. It reflects the world that you thought you knew so well back to you as something unfamiliar and possibly so so so very fucked up.

Join us for our STAGED series, and perhaps consider throwing us a bit of your surplus capital to support it. Help us bow your head.

(Oh, and this.)

(And definitely this.)