NEWS

Sky Macklay: Escalator

Sky Macklay’s new piece for Dal Niente, to be premiered at Party 2018 on June 2nd, is a double concerto for oboe and horn that the composer has described as “wacky”. Violist Ammie Brod skyped (well, google hangout video chatted, because she’d forgotten her skype password) with Sky about mega-instruments, people movers, and her dual roles as a composer and performer of new music.

Ammie: So your new piece for Dal Niente is called Escalator! That’s such a fun name, and I’d love to hear more about why you chose it.

Sky: Well, I think this piece has a lot in common with the multitude of experiences you might have while riding on an escalator or moving walkway: accelerating, getting blocked by people, stopping and starting, and the whiplash of getting off. The musical material plays with drastic accelerations and decelerations of energy and dramatic directional stuff, sharp ups and downs.

*Cue dramatic story about dog poop, a moving walkway, and the horrifying confluence thereof*

Ammie: Wow! Well, back to the music, now that I have a new and very vivid little mental movie to reflect on... Can you tell me more about that musical motion and overall structure?

Sky: The piece basically has three sections. In the first, the horn and oboe play together to form a sort of mega-instrument (interviewer’s note: YESSSS), starting simply with a sort of sad little three-note descending gesture. That gesture gets expanded through a transparent and additive process, getting longer and more heterophonic as other instruments join and start decorating the same expanding phrase. It’s like the steps on the escalator: you start on one, but as you go up or down there’s a longer and more advanced line of them marching out behind you.

The second section starts fast and aggressive, lots of overblown low notes and playing up and down in a single overtone series, and then gets slower and more drone-y as it continues. As it moves into the third section there’s more back and forth between the oboe and horn inside of increasingly perceivable compound meters, jaunty bouncy gestures. The horn and oboe dialogue back and forth with the horn playing pitches related to the oboe multiphonics, and the strings are in this kind of weird A-minor circle-of-fifths thing, coming together briefly for chords that immediately dissolve upward into noisy clustery gestures. The whole thing plays with tonal information from the oboe multiphonics, and starts in the world of metered classical music but then goes to weird places from there.

Ammie: Why horn and oboe? I mean, I love it, but that’s not a combination that I get to hear a lot of.

Sky: When I started talking with Dal Niente about this piece, you expressed interest in writing for some of the less-programmed instruments in the ensemble, and since I play the oboe and I knew Matt and Andy would be down for anything it seemed like a logical choice. I also included harp and guitar for the same reasons, and as it turns out they’ve ended up acting as the kind of disturbing force within the string section.

Ammie: Matt and Andy are totally down for anything! I do know, though, that you’ll actually be playing the oboe solo for the premiere. Can we talk a little bit about what it’s like to perform your own music with other people?

Sky: Sure! I actually perform my own music pretty regularly with a group that I play in called Ghost Ensemble. I wrote a piece called 60 Degree Mirrors that we play regularly, and I’ve enjoyed that because I know so intimately what I want from the parts, and my part in particular, and I can make changes and add small details on the fly as we play it more times. In some ways it’s a lot easier than playing music by other composers, because I know just how flexible I can and want to be with the music.

Ammie: A related question: has that experience changed your relationship to other performers who are playing your music?

Sky: I really like asking for and hearing performers’ opinions. Sometimes performers will have a better way to get to the idea that I had when I was writing the parts, and discussion is a good way to ensure that we all know what that idea is. I’m really open to that discussion, and I definitely want it to feel like I’m welcoming others to the conversation.

Sky Macklay’s new piece, “Escalator”, will premiere on June 2nd at Constellation Chicago as part of Ensemble Dal Niente's Party 2018. This commission is generously supported by the Fromm Foundation.

Shadow Puppets, Giant Domes, and Pierrot Lunaire

Soprano Carrie Shaw opens up about her new staging of Pierrot Lunaire, to be performed at Dal Niente’s June 2 Party.

The centerpiece of Party 2018 is both old (relatively) and new (to us, anyway). For an ensemble dedicated to bringing the newest of new music to our audiences, how much weirder does it get than performing Pierrot Lunaire, written by Arnold Schoenberg in 1912? Violist and social media guru Ammie Brod went to Carrie Henneman Shaw, the brains behind this restaging of a classic work of contemporary music, to get a better idea of what she has in store for Chicago.

Ammie: So I keep hearing things about, like, shadow puppets and giant domes and things. Yes? Please say yes.

Carrie: Yes! When we started talking about this project I knew that I wanted to do shadow theater, and also that I wanted to find ways to use Constellation's stage dimensions in an interesting way, which means a larger-scale production than anything I’ve attempted in previous performances.

I have a friend in Minneapolis, Lizz Windnagel, who is involved in puppet theater and who agreed to work with me, and we decided that we wanted to project shadows onto a dome, kind of suggesting the moon, because that plays a big role in the piece. So I went and bought a garden tent (basically the bones of a greenhouse), and we’ve been building this 9-foot-tall dome that will have shadow puppetry projected onto it during the show.

Ammie: Awesome! What kinds of puppets are we going to see?

Carrie: Well, there’s this really tall bird puppet. It’s really cool, and concertgoers will be able to bid on it during the silent auction at the concert. Also, there’s a crone moon, a forest, and of course, a Pierrot. Lots and lots of puppets.

Ammie: *thoughtful contemplation*

Ammie: I remember you telling me that you were going to be working with a choreographer at Avaloch Farm while you worked on your ideas for this staging. Can you tell me a little bit about that?

Carrie: Yes, I worked with choreographer Penny Freeh in September. We talked a lot about my approach to movement, and how that will affect how I interact with the puppets, and it was really helpful for me to talk through the show with somebody who wasn’t familiar with the piece. We watched a lot of videos of other productions, which was really interesting for me because I’ve done a lot of training in the more classical Renaissance-style commedia dell’arte style of performance but most productions are geared more towards a sort of mime/Parisian clown thing. And while that’s probably more like what Schoenberg might have been seeing when he was writing this piece, I think it’s missing some important parts of the original commedia character identities.

Specifically, I think contemporary readers don't realize how important class was in defining commedia characters and how audiences understood them. In commedia, there are masters and servants - for example, a rich young widow and her principal servant Pedrolino. The widow is funny because she's vain, volatile, and powerful. Her servant is funny, in part, because he has to serve this person who is all of these things, but also because he has peculiarities that draw attention to ways in which he could never belong in the ruling class - his lack of heroism and bravery, his ridiculous clothes, his total dependence on 'service' as his one marketable skill. Both can win and lose a battle here and there, but lower class characters are ultimately pawns in their masters' games, hoping to come out with an extra loaf of bread or maybe a kiss from Colombina. The audience is meant to be deeply invested in the heroic lovers getting together by the end of the play. But Pierrot being hungry? Pierrot being conscripted into the army and being totally hapless as a soldier? We're not supposed to feel too worried about that. Pierrot being beaten, Donald Duck getting hit on the head with something: it’s the same idea.

Ammie: Okay then. How is that interpretation going to factor into your approach to this performance?

Carrie: Well, I wanted to shift away from the usual 'clown' angle, and I got to thinking about parallels between the way in which commedia becomes dark humor in the hands of 20th-century artists and contemporary dark humor, particularly the ways some parts of our own culture seek to defang us.

Ammie: What are you excited for in this project? And do you have any final thoughts for us?

Carrie: For Dal Niente to play a piece of straight-up early 20th century music is a new thing; it pushes us to explore a different type of music and performance together than we usually do. What will it be like to play relatively old music with this group of people? What happens when we juxtapose the old(er) and very new? What do we, as early 21st-century performers, bring to a piece from more than 100 years ago?

Shaw’s restaging of Pierrot Lunaire takes place June 2 at Constellation Chicago as part of Party 2018. Pierrot is the final act of STAGED, our season-long series of interdisciplinary projects involving theater, dance, opera, and (woohoo!) shadow puppetry. More information about Party 2018 and ticket info here, and more thoughts from conductor Michael Lewanski on why Pierrot is, in fact, new music can be found in this scintillating blog entry.

The Body of the State: Snippets

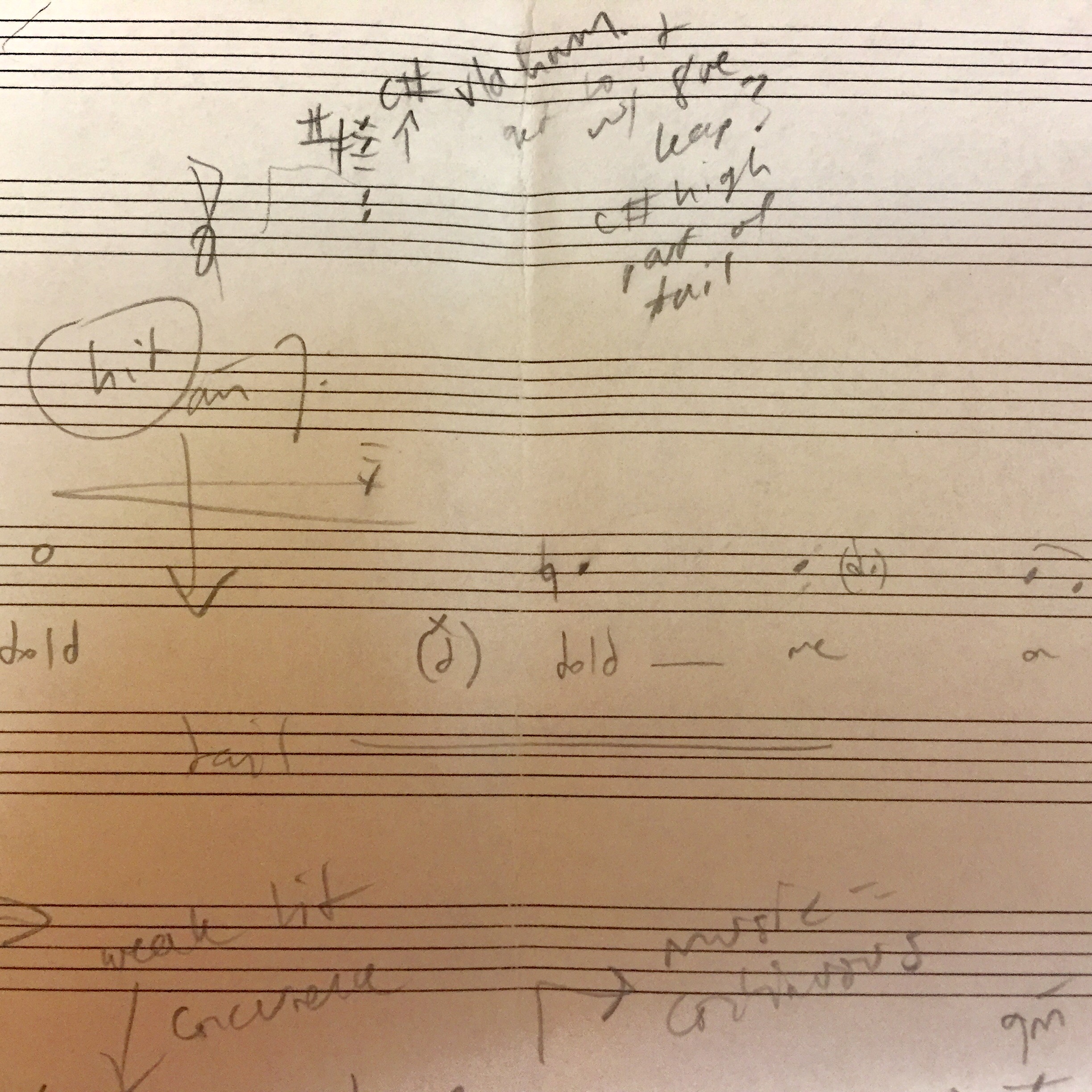

Eliza Brown's The Body of the State premieres on October 20 at the EDGE theater. Here, the composer shares a handwritten sketch of part of Scene III and an audio clip from her recording session at the Indiana Women's prison.

Handwritten manuscript from The Body of the State, Scene 3

Harp, Dancers, Piano: Interview with Tomás Gueglio and Ben Melsky

We sat down with composer Tomás Gueglio and harpist Ben Melsky to talk a bit about Tomás’s new work Proa and working with dancers from Delfos Danza Contemporánea.

We sat down with composer Tomás Gueglio and harpist Ben Melsky to talk a bit about Tomás’s new work Proa and working with dancers from Delfos Danza Contemporánea.

Tell us about the piece. What are the metaphorical and aesthetic materials that you’re interested in exploring in Proa?

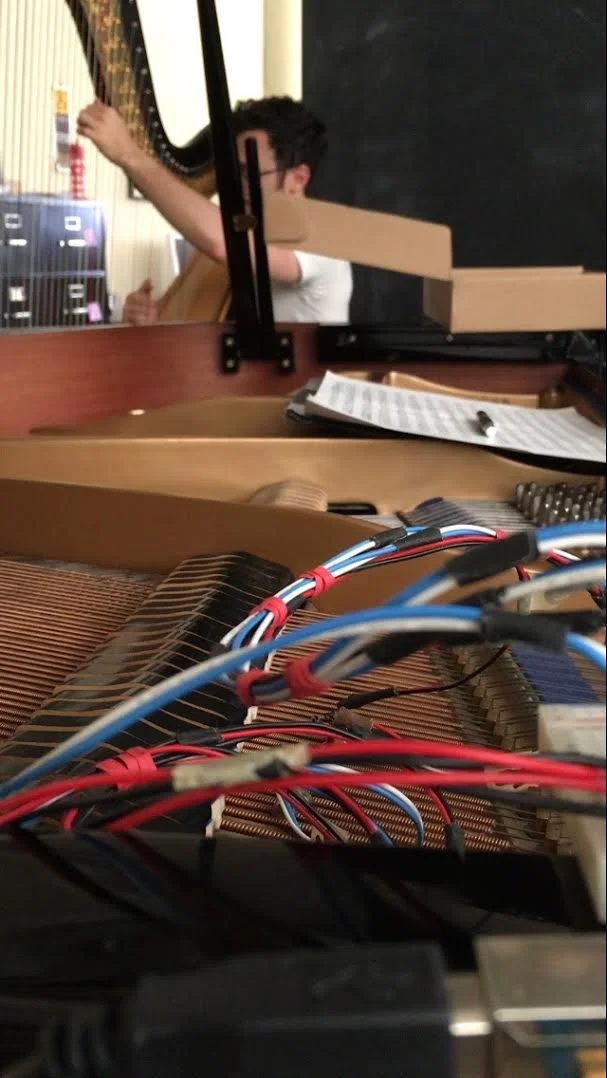

T: Proa will be a piece for four dancers, harp, and piano (without pianist) lasting approximately 30 minutes. The sound world I am imagining is in line with my current tendency of writing immersive textures and landscapes. The work is still in the early stages of the composition, but in the initial conversations with Claudia (choreographer) and Ben we came up with a few guiding concepts to use as jumping-off points. Some of these concepts refer to common tropes in music and dance (water, lyre...) but others connect to issues that are not as picturesque.

What interests you about joining the harp (played by a live harpist - Ben) and piano (controlled by vibrating cell phone attachments in the strings)?

T: This goes back to the previous question. After talking to Claudia, I began to picture an overall sound for the piece. It occurred to me that, to realize that sound, I could start experimenting with samples of two previous works of mine: the second movement of a piece for solo harp, Felt, and my Nokia Etude #3, which is a work for piano that employs a device made of cell phone motors. Both pieces are quite textural and I had the suspicion that they could mix well, with the piano providing further nuance and complexity to an already rich harp resonance. I also like the theatrical idea of having two instruments on stage with one of them being played by an invisible performer. I think it goes well with the poetics of the piece.

Working with dancers (or with actors or other types of artists) often brings a categorically different approach to the rehearsal process. Can you speak to your past experience working with artists across disciplines and how the rehearsal process produced a different result?

T: I would say the approach varies depending on the specifics of the project and the group of people working on it. Regarding the rehearsal process, my default attitude is to defer to the disciplinary idiosyncrasies of the people I am working with. The do’s and dont’s of rehearsing with, say, actors are different from the ones of rehearsing with musicians and I try to be respectful of that. In the case of my previous collaboration with Delfos, the final product was the result of a series of improv sessions where there was not a clear compartmentalization between composing, choreographing, rehearsing, and performing. They all happened somewhat simultaneously.

B: Most music performances follow the same general script - you prepare your part, show up at the first rehearsal (often just a few days before the performance) rehearse intensely for a few hours a few times and then perform. Working with dancers or actors is a very different approach; the group learns the work together rather than individual learning fastened together in rehearsal. Musicians’ training often means that one’s part should be basically performance-ready by day one. By comparison, in theater or dance on day one you really don’t know too much about the final result. The journey from start to finish is a long, complicated, often more vulnerable one.

I think another important thing that musicians can learn from this rehearsal approach is actually how it relates to performances. By habit, we’re quite used to the general premise of a single performance. Multiple performances offer a sense of fluidity and development within the performance cycle itself. A show will change and evolve over the course of several performances, offering opportunities to discover different moments or ideas within the piece.

In past work (On Love, After L’Addio, String Quartet...) you engage with historical texts or refer to outside source material. What interests you about that dialogue and do you anticipate similar treatment of outside material here?

T: I believe it is more parasitism than dialogue but yes, this engagement with historical texts is a recurrent feature in what I do. Following this line of thought, I would say my interest in intertext is quite utilitarian, in that the borrowed material provides a referential anchorage out of which one can unfold a chain of materials and associations. For Proa, I am considering using some borrowed music but the amount of texts that can relate to things like ‘water’ or ‘lyre’ is so vast that I am having a hard time deciding. In any case, I know that if I end up working with pre-existing music there is a strong possibility that the borrowed material will encapsulate features that are not necessarily present in the music that is not new, like a negative image of the not-borrowed music.

How do you feel about having more of a role of composer/improvisor throughout the collaborative process? How do you feel about being onstage with the dancers?

B: This is kind of a new thing for me. While there is always a sense of improvisation and play working in individual composer sessions, I think this will be more than a bit different, if for no other reason than there will be one harpist, one composer, and four dancers all working together. I’m eager to see how ideas translate between the mediums, how the dancers interpret timbre, harmony, texture, etc. into their work and how watching their process will change my perspective of sound and its function within the piece. The Delfos dancers are first and foremost improvisers, so I am eager to see how we learn to anticipate each other’s moves and coordinate throughout.

Links:

Nokia Etude #3 https://vimeo.com/123471987

Poster design by Santiago Fernandez

Old New Music: Pierrot Lunaire and the Chocolate Factory

Conductor Michael Lewanski delves into the New Music-ness of a not-so-new New Music classic, and translates some German in the process.

By Michael Lewanski, conductor

Serenade, the 19th of the 21 songs of Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire (actually, the composer calls them “melodramas”—which, upon reflection, totally feels accurate, even given their miniature size) is even more meta-musical than the others. (And that is really saying something. Pierrot has got to be one of the most desperately self-conscious pieces in historical music, making heavy-handed use of a dizzying number of past genres and composers: Chopin (explicitly named in a title), the waltz, the menuet, the passacaglia, the barcarolle, the rondo, all manner of Baroque counterpoint, a bunch of others I can’t keep track of because of aforementioned dizzyingness). Anyway here’s the text of Serenade, in my own not very good translation because I don’t really speak German:

With a grotesquely outsized bow

Pierrot scrapes on his viola,

Like a stork on one leg,

Sadly he plucks a pizzicato.

Suddenly Cassander’s here—frenzied

by the nighttime virtuoso—

With a grotesquely outsized bow

Pierrot scrapes on his viola.

Now he throws aside the viola:

With his delicate left hand—

He seizes the bald man by the collar

Dreamily he plays on the bald spot

With a grotesquely outsized bow.

On the one hand, this is an eccentric, kinda creepy, actually-a-bit gross fantasy, the sort of thing that shows up randomly in your dreams between an appearance of your long-dead first pet and your cisgender, heteronormative, right-wing uncles dressed in matching drag singing a song from Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory. Less weirdly and more generally, another way to construe it is as a description of the project of new music at its best, though I hasten to add that we definitely don’t always live up to it. I know you’re skeptical but stay with me: in what we do, as new music people, something unexpected might happen to an instrument, or to a sound, or to a genre; this thing might be disruptive, causing you metaphorically (or literally) to stay awake at night; when you try to interrupt us, though, rather than stop, we make you the instrument. Put another way: when we do things right, new music is an art form that bows your bald spot. It does funny things to how your head feels.

Like I said, we don’t always live up to it; more often than not we don’t. Life is tough under Trumpian nepo-capitalism, where some people's nauseatingly rich family members and friends get more nauseatingly rich and more, well, straight-up nauseating; and everyone else is srsly just trynna make a buck. Thus, it’s easy for new music to just, like, play music, cross our fingers, look pretty, smile wide, and hope y’all like us [gritted teeth emoji].

“[I]n what we do, as new music people, something unexpected might happen to an instrument, or to a sound, or to a genre; this thing might be disruptive, causing you metaphorically (or literally) to stay awake at night; when you try to interrupt us, though, rather than stop, we make you the instrument.”

But, as a project by a new music ensemble, it’s nice for Dal Niente’s STAGED series to remember the example of Pierrot Lunaire. Of course, Pierrot is SO not new music; it was written in 1912, before World War I, in a world hopelessly smaller, whiter, more patriarchal, and more racist than our own. (Yeah, tbh, maybe not more racist.) But on the other hand, Pierrot is SO new music; if anything, it’s new music’s prototypical work, and a self-consciously prickly one. There are some obvious details: here’s a boring history lesson about blah blah blah one-of-the-earliest-examples-of-free-atonality, whatever; there are IMPORTANT INNOVATIVE IMPORTANT uses of instrumental important techniques that are innovative and important [eyerolling emoji]; and last but certainly least: the typical new music instrumentation (violin, cello, piano, clarinet, flute) is named after it (“Pierrot plus percussion” comes out of a new music person’s mouth about as much as “accessible” or “impactful” or “post-minimalist” or “why didn’t we get that grant” does). But gosh, it’s so much more and so much better than IMPORTANT AND INNOVATIVE early examples of free atonality. It, like, doesn’t, like, always sound good. It’s uncomfortable. It’s tortured. It makes directly contradictory claims about its status. For instance: what’s the deal with that idiosyncratic singing? Is it actually singing? What is singing anyway? Worth remembering: it was commissioned by a person (Albertine Zehme) who was not actually a professional musician or singer, but an actress. The sprechgesang (spoken-sung) or (more commonly) sprechstimme (spoken-voice) style of the vocal part is simultaneously alienating and familiarizing. It’s more natural than classical singing (which, let’s be honest, is zero percent natural), but also is not imitative of everyday speech either. You might feel yourself drawn to sprechstimme at the same time that you find it repulsive or abject. It somehow recapitulates what you do when you speak, but it’s much more wretched and intimate and violent and embarrassing—it’s the id to your everyday language’s ego.

Speaking of dilettante pscychoanalysis, maybe what I want to really say is that Pierrot Lunaire is the id and the superego in the same piece. (It would be difficult to imagine that Schoenberg wasn’t influenced (even if—wait for it—unconsciously (see what I did there?) by Freud’s ideas, which were floating around early 20th century Vienna). It performs more than its share of strange, terrifying, for realz bizarre, free-associative fantasies: decapitation by the moon, ginormous moths that blot out the sun, smoking in a person’s skull, returning to a long-absent-from home (one that, hmmmm, actually you’re not quite sure you’ve ever been to now that you really think about it wait was my childhood real actually did any of us actually have childhoods wait are still all children whoa). But at the same time, it wears the rigor of its organization on its sleeve as so much a point of pride that it feels defensive and trying-too-hard: it is the composer’s Op. 21, and it’s 21 songs, begun on March 12, 1912; but it’s not just 21 songs, it’s “Three times Seven Poems” (according to the title); seven-note motifs are used throughout the work, including the famous piano opening; there are seven musicians that perform. Pierrot Lunaire overly insistently promises you, sugarily, that your listening experience is structured.

Maybe I’m skipping a step here, but I feel like Pierrot Lunaire is the perfect work for a new music ensemble’s series about the stage not because of its IMPORTANT INNOVATIVE IMPORTANCE OF INNOVATION, but because it masterfully performs the therapeutic functions that are the reason we go to the theater, and it does so in a way that is fundamentally musical. It is both hyper-real and deeply fake. It mirrors your contradictory experience of existence. It reflects the world that you thought you knew so well back to you as something unfamiliar and possibly so so so very fucked up.

Join us for our STAGED series, and perhaps consider throwing us a bit of your surplus capital to support it. Help us bow your head.

(Oh, and this.)

(And definitely this.)

Interview with Eliza Brown: Epistemic Injustice, Juana of Castile, and the Women of Indiana Women's Prison

“My bondage shall not / keep my story bound

”

In this interview, EDN violist Ammie Brod sits down with composer Eliza Brown to ask some questions about The Body of the State, Brown's new monodramatic work that Ensemble Dal Niente will premiere as part of its STAGED series in 2017-2018.

Q: First off, can you tell us a little about the history behind your monodrama?

A: The Body of the State is a monodrama for soprano and ensemble about Juana of Castile. Juana, born in 1479, was the daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella, the rulers of what is now Spain. At 16, she was married to Philip of Burgundy, who soon proved abusive and unfaithful, denying Juana power in the household and locking her in her chambers as punishment.

In 1506, both Isabella and Philip died, leaving Juana, at age 27, sole heir to the Castilian throne. She found herself locked in a battle for power with her own father, who strong-armed her into signing away her governing rights, leaving her queen in name only. Rumors of her insanity were spread by her political enemies, and her father had her confined to a house in Tordesillas, surrounded by servants and priests whom he paid to lie to her, control her, and interrogate the legitimacy of her faith

Q: That’s very . . . operatic, isn’t it?

A: It is, and that’s part of what got me interested in Juana’s story. I was initially drawn to this as a “hidden narrative” of women’s history, the dark origin story of the Hapsburg empire. But I also appreciated its operatic-ness: the scale of its drama, its emotionally fraught scenarios, the family power plays that affect thousands of people, and as a composer I was interested in the opportunity to allude to and subvert the operatic trope of the madwoman.

Q: Has the focus of your interest changed as you’ve delved deeper into the story?

A: It has, for a number of reasons. As this project developed over the last few years, Juana’s story came to feel more and more relevant to the modern world. Women are still used as political pawns via arranged marriages. The stigma of mental illness is still used to discredit the voices of survivors of abuse and oppression. Educational disparities still undermine the human potential of women and girls around the globe. Incarceration is still used as a method for controlling the non-conforming and the politically threatening, and women still face intense opposition when they pursue political power. This is not only a historical story, but a human story.

Last fall I was involved in a faculty/staff reading group at DePauw University which met via videoconference with the graduate class at Indiana Women’s Prison. We read articles by philosophers and by women in the prison about the concept of “epistemic injustice.” Epistemic injustice occurs when we discount someone’s ability to be a knower, reducing that person to a knowable object. This form of injustice affects many marginalized people, including the incarcerated. As I learned about epistemic injustice from the women at IWP, I felt it perfectly described Juana’s situation. This changed my understanding of the character, and of the text and music she ought to sing.

I felt an ethical responsibility to tell the IWP scholars that their work had influenced mine, and an ethical desire to offer them a way to participate in this project as a small corrective to epistemic injustice. A number of women were interested in participating, and we scheduled a series of meetings to discuss the form that might take.

“

The body of Juana of Castile is likened unto a strikingly luminescent orb. An orb floating about the land of her people, equally tangible and intangible, equally desired and repulsed, beautiful, but hard to look at, hard to take in....In the story of power misused against her and the dilution of her own power, we see a woman who had no real possession of her body.”

Q: There are so many levels of collaboration going on in this project! Can you tell me more about the form that this specific collaboration ended up taking?

A: It was important to me to approach this particular collaboration in a way that minimized the position of power I was systemically assigned to, so at first I asked a lot of questions: how do we do this together? Initially, we discussed excerpts of a book about Juana, and then the women wrote responses to it in the formats that felt most appropriate to them. We picked through these responses together, editing and combining them into a libretto. We went through several rounds of editing, giving feedback, and then editing again.

More concretely, I wrote the libretto for the second scene before the collaboration; the librettos for the first and third scenes were written with them. We have no text actually written by Juana to work with, despite her presumed education; all we know of her life is what other people wrote about her. Much as I wanted this monodrama to subvert the operatic paradigm of the mentally unstable female, I wanted this collaboration to subvert the epistemic injustice that prisoners, including both Juana and my collaborators, experience on a daily basis.

Q: Aside from the concrete contribution of a libretto, were there other ways this collaboration shaped your piece?

A: Absolutely. The piece now includes aspects of Juana’s story and psychology that I had not prioritized. For instance, the character now mentions her children several times, and at one point mistakes someone else on stage for one of her sons. I had initially planned to leave out references to her children for the sake of theatrical simplicity, but the women thought we had to find a way to include them.

Our conversations also complicated my perception of Juana as a constant victim. My collaborators picked up on her ability to maintain small forms of resistance to injustice, even if that resistance was sometimes to her detriment. They saw her as strong, because she’s aware of the injustices in her world and resists them instead of being broken by them. Juana heroically attempted to assert her agency against all odds, despite losing battle after battle and despite the opposition of everyone around her. Her story is simultaneously tragedy and triumph.

They’ve also had a hand in the sonic world of the piece. Juana’s mental health is somewhat ambiguous in the historical record: was her mental instability innate, or imposed by circumstance? Some of the women I’ve been working with have had personal experiences with mental health that are not unlike Juana’s, and this prompted a discussion of sound and what sounds could be used as triggers for or symbols of her mental instability within the scope of the piece. Some of these--an electric guitar string being scraped while a flute plays a particular sound, for instance--will be included in the final score. I will also record the women’s voices and incorporate those recordings into the electronics, and I’ve invited them to choose some of their individual text responses to the subject matter that can become part of the background info surrounding this piece. [Two of these texts are quoted above.]

Q: Any final words on this collaboration or your work in general?

A: I’d just like to thank the women I’ve worked with at IWP for their insights into Juana’s story, and the education program at IWP for approving and facilitating this project.

Interview with Katie Young: Piecing Her Together

violist Ammie Brod and composer Katie Young sit down to talk about Young's upcoming work, When Stranger Things Happen.

“Think of the underworld as the back of your closet, behind all those racks of clothes that you don’t wear anymore. Things are always getting pushed back there and forgotten about. The underworld is full of things that you’ve forgotten about. Some of them, if only you could remember, you might want to take them back. Trips to the underworld are always very nostalgic. It’s darker in there. The seasons don’t match. Mostly people end up there by accident, or else because in the end there was nowhere else to go. Only heroes and girl detectives go to the underworld on purpose.”

In this interview, EDN violist Ammie Brod sits down with composer Katie Young to ask some questions about When Stranger Things Happen, Young's new monodramatic work that Ensemble Dal Niente will premiere as part of its STAGED series in 2017-2018.

Q: Your piece, When Stranger Things Happen, is inspired by Kelly Link’s short story, The Girl Detective. Can you tell us more about that connection and why you felt moved to work with this particular story?

A: Well, I love Kelly Link’s work, and I have a long relationship with her writing - I first read her in 2005. This particular story deals extensively with loss and searching: for objects, for people, for experiences we can’t regain. But it deals with these heavy experiences in a way that’s both highly stylized and yet somehow still charmingly playful, and I really liked those contrasting elements. I also got kind of obsessed with an image from the story, or maybe an image that I invented for myself after reading the story so many times, of Amelia Earhart’s plane on the bottom of the ocean, surrounded by lost objects in a dreamy drifting space.

The structure of the story is really dynamic and has been a big influence on the form of my piece. The story is very structured but also has a highly fragmented, non-linear quality that informs the structure of my piece and the way it explores its soundworld.. The detection that we’re doing is sonic.

Q: Can you talk more about that last part? How do you communicate a story sonically?

A: I decided pretty early on that I was going to steer clear of a direct retelling of the story itself, but I want to translate some of the larger ideas from the story into the music. Mirroring the loss, detection, and creative reassembly that the Girl Detective moves through in the story, the music also works through these processes.

For one, I knew the monodrama was going to incorporate three stand-alone pieces that I was writing: one for solo electric guitar, one for mixed ensemble, and one for percussion quartet. These pieces work as source material that will be fragmented (“lost”) and recombined to create the larger work.

One of my favorite parts of the story are these lists of lost (and sometimes rediscovered) objects that pop up throughout. I compiled a list of all of them and considered how they could be used to actually make sounds. For example, Amelia Earhart...she’s missing. I thought about propeller blades of her airplane and extrapolated that out to fans. Fans are used throughout the piece to create sound - on the guitar, on their own as prepared objects, or even just by bumping the spinning blades up against the music stand.

Excerpt from Katie Young's list of lost (and sometimes rediscovered) objects that pop up throughout The Girl Detective

Spending all this time thinking about these lost objects from the story got me thinking about things I’ve lost - insignificant things like my keys or actually very meaningful things like a piece of jewelry my mom gave me. And then, of course, we lose people, relationships, parts of ourselves, our teeth!...

I work best in collaborative scenarios - getting to know people better is one of the things that keeps me doing this whole music thing - and so I invited the performers to submit their own lost objects to the list, with stories if they wanted to share. Then I chose objects from the various lists that could either be used as preparations for traditional instruments, as sonic objects in and of themselves, or as metaphorical representations of less concrete concepts. For example, the electric guitar is prepared with bobby pins, pieces of jewelry, fans, playing cards...

objects used in electric guitar preparation

Q: What are you excited about regarding the final production?

A: We have an amazing group of women working on this project that I am super excited to work with: Eliza Brown is writing an incredible work that I can’t wait to experience. Amanda De Boer is such a compelling presence on stage, with such a beautiful voice and brings deep thinking and creativity to the project. And Emmi Hilger, who’s directing, possesses a clarity that has already proven so inspiring for me. I can’t wait to see what we all come up with!

-Ammie Brod and Katie Young

Interview: Murat Çolak's SWAN

In February of 2017, Ensemble Dal Niente premiered Swan, a sprawling piece for seven musicians and electronics. Here, composer Murat Çolak takes us behind the scenes.

In February of 2017, Ensemble Dal Niente premiered SWAN, a sprawling piece for seven musicians and electronics. Here, flutist Emma Hospelhorn and composer Murat Çolak take us behind the scenes.

SWAN appears on our upcoming album, object/animal, out March 25, 2022, on Sideband Records.

Which came first, the piece or the title? What are the central themes/ structural elements of this work?

SWAN existed as a concept long before I wrote the piece. About a year ago, I was working on some dance music - a downtempo track with an extremely emotional chord progression and warm, sweeping synth stabs. I was imagining it as the soundtrack to a fashion photo shoot. I named it SWAN, imagining an elegant, charismatic creature floating on the water, alone. The swan is iconic, it has personality and vibe. It has power. Being fancy, being as beautiful as a swan in a rough world is power to me.

In (the new) SWAN, I wanted to focus on the music I am passionate about, on the culture I am passionate about. And the imagery too - every single part of this piece comes directly from my experiences, from my artistic, spiritual, and social identity. SWAN is an emotional piece. It was challenging to write, because I think of this piece (for the most part) as a farewell to my previous, mostly-borrowed, practices. I am claiming my own space. I thought it would sort of pull me away from the community I’ve belonged to for the past seven-eight years because, you know, this is fancy music: it is pop, it is beautiful, it is like a swan. In this sense, I think SWAN embodies the power I see in the iconography that inspired it.

To answer your question more directly, SWAN is not a thematic work. It is beautiful and fancy; it is pop, it is new, it is music.

The score comes embedded with several really cool images, including a calligraphic tiger. We performed the piece alongside a video created by Dan Tramte. Can you talk a bit about your inspiration for the visual imagery of this piece, and how the visuals fit in with the sound world you've created?

The images are a kind of collection of the things and the world that inspired SWAN. The collection included a calligraphic lion (I am a big fan of felines - like swans, they are charming, charismatic creatures) by the Turkish calligraph Ahmed Hilmi, another calligraphic lion titled ‘The Lion of God (Allah)’ symbolizing Caliph Ali (Ali is aka ‘The Lion of God’ in Islamic literature), a calligraphic swan titled ‘The Swan’ by Yahya Muhammad which is a Basmala/Bismillah [‘in the name of God (Allah), the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful’ - the opening phrase for each chapter of the Qur’an, and the most commonly used motif in islamic calligraphy], beautiful swan pictures taken by my mom, some fascinating pictures of highly geometric details of Islamic architectural pieces taken by Eduard Wilmer, alongside some others. Prints of works by Hilmi and Muhammad come with the score as inserts since they were strong inspirations for SWAN.

From the above, you can probably tell that I am fascinated by Islamic visual arts and how animal figures function in them. Islamic art is not representational. A swan is beautiful, a lion is beautiful, but they are only meaningful because they ‘are’, because they exist as realized visions of the Creator. Attempting to replicate a creature with technical realism, artistic or otherwise, is considered to be “shirk” (idolatry, polytheism). So instead, one might present the creature through pictographic calligraphy which, most of the time, reads 'Bismillah', 'Muhammad' or ‘Allah.’ The animal figures themselves are aesthetic-spiritual concepts. Though I am not practicing religious iconoclasm, I too am uninterested in the narrativity of my images. They are there for vibe, they are there for spirit. I am simply and singularly interested in their beauty.

I worked on the concept videos with Dan Tramte (a composer/multimedia artist and a good friend of mine). I’d been following his work for awhile, especially on his social media accounts (which he successfully curates as artistic media), and from a stint in January when we worked together in our close friend/collaborator Marek Poliks’ interdisciplinary show The MAW. Dan had made live video for that show, and I (all of us) loved his work. And since day one, I had been thinking of expanding the medium of SWAN. So I talked to Dan, showed him the images I had collected, and he came up with these amazing videos. So, yes, the short videos mark the sections of SWAN, ground the piece’s conceptual and spiritual content, and (most importantly) contribute to the world / the vibe of SWAN. We are debating adding more video in future shows.

The electronics in this piece are like nothing I've ever experienced. They included field recordings, sonic sculpture, and a bona fide trance track. How did you create the electronics? I'm asking this both in terms of structure and as a sort of semi-tech-literate person who really wants to know, like, HOW you made it.

SWAN is about going out: going out to the street, to the club, to a ritual, to a party or a funeral. It’s about real places with real people, but less about the realities of these places and more about their vibe. It’s about getting out of home, the studio, the institution, going to places where people connect and do things, sing, dance, laugh, cry, perform, celebrate, and connect. The music of SWAN, the electronics, come from ‘outside.’

SWAN’s aesthetic is a blend of Turkish/Islamic and pop-cultural elements. The opening section, Korridor, is a drone/ambient movement with a big trance synth part. It is ritual music. It’s big, dense, heavy, and it moves slowly, like lava. It blankets you and burns you slowly. Karaoke Mahshar is some sort of a Turkish Trance-Pop hybrid. It is a very melancholic, dark piece of music. The instrumental choir sing an emotional pop/“fantasy music” (a Turkish genre) melody in unison over a flamboyant electronic track. It’s the soundtrack to a club for the wasted, for emotional after-hours karaoke. The final section, Rod Modell, is a dub-techno flavored ambient movement. It is the sound of a huge, postapocalyptic mosque - a mosque sunken in chalky waters. Rod evolves to a big, stretched monophonic melody, coming from a very old vinyl, a song from the old times. It finally

cadences to a highly processed “tilâvet” (the Swan) which was recorded during an actual funeral ceremony in the summer of 2016.

I worked on the electronics and the score simultaneously. So, neither came first, it was a single process. I produced, mixed and mastered the electronic part (and the recording of the performance, too) completely digitally in my digital audio workstation. Materials varied from hardware and virtual synths to sample libraries, from little studio recordings to field recordings that I found/made. I also made patches for an analog monophonic synthesizer which the pianist (Mabel) played. This piece was a big learning experience for me, not only in terms of electronic music production, but specifically the techniques and technologies of writing for live instruments and electronics.

Followup question: how do you see the relationship between the sounds produced by live (mic'ed) instrumentalists and the electronic sounds? At one point during rehearsal you said that we (the band) were "an acoustic ring modulation." Can you talk more about that?

The electronics give SWAN its world. They bring virtual space, they bring vibe. But this world is lifeless without the performers’ presence. Without them, it’s just a maquette. You guys are the life in the SWAN-world; you are the force that makes it a real place, that turns the maquette to real music.

SWAN might also take the new music performer out of their comfort zone. The performers play rhythms, chords, melodies, and their efforts are subject to the constraints and exposure of a strict time grid. Though the parts themselves are not too complicated to execute or understand, a single flaw can feel extremely visible. Further, I am asking the performer to really understand these materials through the aesthetics of the SWAN-world. SWAN’s history clashes with the history of the western concert performer. So I think there is a little adjustment, or at least a little productive tension.

Ring modulation is basically the multiplication of two electronic signals with simple waveforms. The result is a metallic, bell-like sound with inharmonic over- and sub-tones. Towards the end of Karaoke Mahshar, I introduce ring modulation in the synth pad, so it gets more and more metallic/inharmonic/detuned. The ring modulated pad also opens Rod Modell and sustains for a while. What I did in the instrumental part was to slowly introduce held out-of-tune tones while introducing microtonal-inflections in the ensemble melody. The beatings, difference/combination tones imitate and extend the ring modulation in the electronic part.

Did any new compositional directions arise for you through your work on this piece?

What's next?

The very next project is an approximately 10-minute long piece with amplified instruments, electronics, and synthesizers, similar forces with SWAN. I’m writing it for this year’s MATA Festival. It’s titled ‘Orchid’. I am working with the aesthetics of SWAN, but probably pushing toward an even more ‘Turkish’ place. After that I’ll be preparing for an installation performance in Denmark.

As I said, composing/producing SWAN has been an invaluable learning experience. Things are getting clearer and clearer. One thing I tried with SWAN was to create an artwork that is a show, an event, a thing by itself rather than simply a piece of music to semi-randomly appear on a new music concert. SWAN should bring its own world - it should kind of curate itself.

Curation and production value are really important for me, and I want to make them a priority in all of my collaborative work. My earliest musical crushes were people who balanced strong aesthetics with equally high-quality production values - people like Janet and Michael Jackson, Donna Summer, Sezen Aksu, Ahmet Kaya, Quincy Jones, Tarkan etc. These people are the reasons I decided to become a musician. My recent heroes, too, belong to the lineage of artists who practice this balance. Some names I can name are Rihanna, Young Thug, and Kanye (I have to insert Rod Modell, too, my favorite composer/ producer - I’ve even named the final section of SWAN after him). These are very high standards, and ones that might feel impossible because of their high financial and logistical floor. Resources are much more limited when it comes to music that is more experimental. But we shouldn’t forget - our institutional affiliations give us opportunities that many aspiring artists don’t have (and that many of our most established artists today did not have at their outset). Given the privileges our musical community enjoys, I think that creating good production values is a kind of a responsibility, or at least I consider it every bit a priority as a strong aesthetic sense. That is to say, for future projects, I will devote as much of my energy to production and curation as I do to composition.

Again, SWAN was about ‘going out’. The door is now open for me and I feel like I can go (out) further. I want to keep composing/producing large scale works with a similar, an even more radicalized aesthetic approach. I’m planning to expand the media, and to collaborate with artists from other disciplines more often. I’ve been discussing/brainstorming several future projects with my collaborators for sometime now. Right now, we’re trying to find contexts (such as residencies) to work on both the art itself and of course the financial/ logistical side of things. Though these projects are still at the conceptual stage, I think I’ll be able to make some exciting announcements in a few months.

Swan was performed on February 19, 2017, at Constellation Chicago. A recording of the live performance can be found on soundcloud.

Dal Niente Summer Camp

On the eve of Dal Niente's LA debut, Soprano Amanda DeBoer Bartlett remembers the last time the group went to California.

By Amanda DeBoer Bartlett, Soprano

The first time I toured with Dal Niente to California, during the late winter of 2014, we stayed at the Hotel California in Palo Alto. We were in residence at Stanford University, workshopping new pieces by the PhD candidates, and they had graciously scheduled us plenty of down time during the week. The snow hadn’t melted in Chicago, so Palo Alto felt luxurious at 70 degrees. At night, after finishing rehearsals, we would sit out on the roof of the Hotel California telling stories, sharing beers, and talking about how strange our little niche of the music industry is. On that tour, I remember finally getting to know Mark Buchner, Dal Niente bassist, and Andrew Nogal, our oboist, even though we’d been in the group together for a while. I remember working with composer Jessie Marino on a piece for solo voice and electronics that is now one of my favorite solos to perform. I remember composer Kurt Isaacson sharing a bottle of Fernet Branca with us while we told ghost stories. Honestly, it felt like Dal Niente Summer Camp.

Performing music by Jessie Marino at Stanford

While prepping for another California tour next week, I am amazed by how much has changed for Dal Niente during the past two seasons. We welcomed a new executive director, harpist Ben Melsky, who is so infectiously cool and uplifting that I swear the ensemble floats while he’s in the room. We released a rad chamber pop album with Marcos Balter and Greg Saunier of Deerhoof. We added new members, took some slick photos with Aleksandr Karjaka, threw a sweet party in our own space, recorded some astounding music by George Lewis. It’s been intense.

Through all the changes, though, this still feels like the group I want to hang out with after a long day of rehearsals. Not only do we all share the same passion for realizing impossible music and mastering our craft, we share a vision for the world that embraces complexity and ambiguity with excitement. Plus, these people have great taste in beer.

after rehearsal with Dal Niente and Stanford composers in Palo Alto

Next week, during our California tour, we’ll be playing rock-solid music by Katherine Young, Greg Saunier, Natacha Diels, Raphaël Cendo, Stephan Prins, Giacinto Scelsi, and Franco Donatoni. It’ll feel like a Dal Niente Greatest Hits Tour because these pieces are so ingrained in our aesthetic identity, and we’ve studied these particular pieces and composers for years. But, it will also feel completely fresh, since this will be a new crowd away from our home turf of Chicago. I’m particularly excited to check out the student composer pieces we'll be workshopping at USC. I love seeing what the next generation of composers is up to.

If you’re in the Los Angeles area, we look forward to sharing some beautiful music with you!

Musicians in Taxis Not Getting Coffee

By Andrew Nogal, Oboist

Now that I’ve slept for approximately 48 hours straight and washed six loads of all-black laundry – the staple of the freelance musician’s wardrobe – I am ready and eager to reflect on the Ear Taxi Festival, no doubt the boldest and most daring musical project I have watched unfold during my many years as a musician in Chicago. From my unusual perspective, Ear Taxi was a triumph of both imagination and execution. While I didn’t get to experience any Ear Taxi events purely as an audience member, I can offer a behind-the-scenes look at my preparation as well as a firsthand account of the convivial backstage vibe.

I performed not only on Dal Niente’s Friday night set, but also on Sunday afternoon as soloist with DePaul’s Ensemble 20+ (conducted by our own Michael Lewanski) and with the CSO’s MusicNOW Ensemble on Monday evening. In the week leading up to the festival, I had several twelve-hour workdays, during which I squeezed two or three rehearsals into days already packed with my usual teaching commitments, practice schedule, and reed-making routine. (I don’t drive a car, and I am grateful to the CTA and Metra for delivering me to almost every engagement on time!)

Months in advance, I knew that Ear Taxi would push me to my emotional and physical limits, and so I made the drastic, uncharacteristic decision to limit my caffeine intake during the festival. If you know me well, you know that this is a big deal. It was in Darmstadt in 2012 that I transformed into the kind of person who drinks coffee at all hours of day and night, and since then, my life has been an avant-garde pinball machine: I drink coffee, I bounce off the walls, I play the oboe. Ding ding ding, new high score! I couldn’t afford to have my nerves or health fail me during Ear Taxi, though, and I trusted that the music-making would be invigorating enough. A tiny cup of coffee at breakfast would be my only caffeinated ballast for about ten days, withdrawal headaches be damned.

That turned out to be a really good decision, because I was right: Ear Taxi enveloped me in positive, productive musical energy of a kind I certainly haven’t felt since I was a student. I was inspired to perform well not just for myself, but on behalf of the entire creative community of which I am a proud and active part. We were given a big, resonant stage on which to stand in front of a large, curious audience. It’s unfortunately rare as a performer of contemporary music to “get presented,” i.e., to have much of the unglamorous but essential legwork of concert production (fundraising, marketing, schlepping chairs and stands, transporting gear, selling tickets) offloaded from us musicians. Festival curators Augusta Read Thomas and Stephen Burns, festival manager Reba Cafarelli, and their whole staff and volunteer team are to be commended for following through on such a comprehensive vision of what this festival could be. Thanks to the host venues, too, for providing exceptional and comfortable spaces in which to work intensely.

And what about the music? It would be impossible to make any sweeping generalization about the programs or artists showcased at the festival. Two possible (among infinite) takeaways from the festival’s programming are that today’s composers and performers are exceedingly willing and able to engage thoughtfully with the music of the past and, secondly, that hostilities have perhaps softened between composers formerly seen as representing rival schools.

Personally, I thought that a lovely classicist thread tied together Ensemble 20+’s two selections: the Oboe Concertino by Bernard Rands set me up as a rhapsodizing protagonist backed up by the band from Ravel’s Introduction and Allegro. Next on the program, Eliza Brown’s watery, whispery A Soundwalk with Resi conjured the spirit of Richard Strauss.

On Monday night, Katie Young’s new piece where the moss glows received its world premiere at the festival’s finale, which doubled as the first CSO MusicNOW concert of this season. It stands to reason that the Chicago Symphony’s average concertgoer has probably never engaged with a piece like this – gnarly and knotted and whirring – performed live before. Dal Niente’s guitarist Jesse Langen described it with his usual aplomb: “maybe you’re somewhere in Portugal with a radio that’s 150 years old with these gigantic tubes coming out the back, and you tune in a faint signal from Dresden and it’s Wozzeck… that’s what this piece sounds like.”

Over the course of the festival, I overheard composers of what we’d generally call post-minimal music praising compositions that might get slammed elsewhere for being inaccessible or academic. It turns out that different listeners bring different life experiences to their seats in the concert hall, and those are hardly ever cut and dried; sounds that one person drably brushes off as “academic” might remind someone else of beats blasting at a warehouse rave. (Yes, I heard these two differing reactions to the exact same piece).

If you attended many of the concerts at Ear Taxi, first of all, thank you for being there, and second, I hope you weren’t expecting to love or connect with everything you heard! Even as a performer, I’m not crazy about all the music I play. Maybe that sounds controversial or surprising, but I believe it’s just a natural part of the great privileges and responsibilities of doing my job. It’s a meaningful and important challenge to try to give new music its best possible first (and second and third) performance. I cared so much about my concerts at Ear Taxi, I was willing to give up coffee for them.